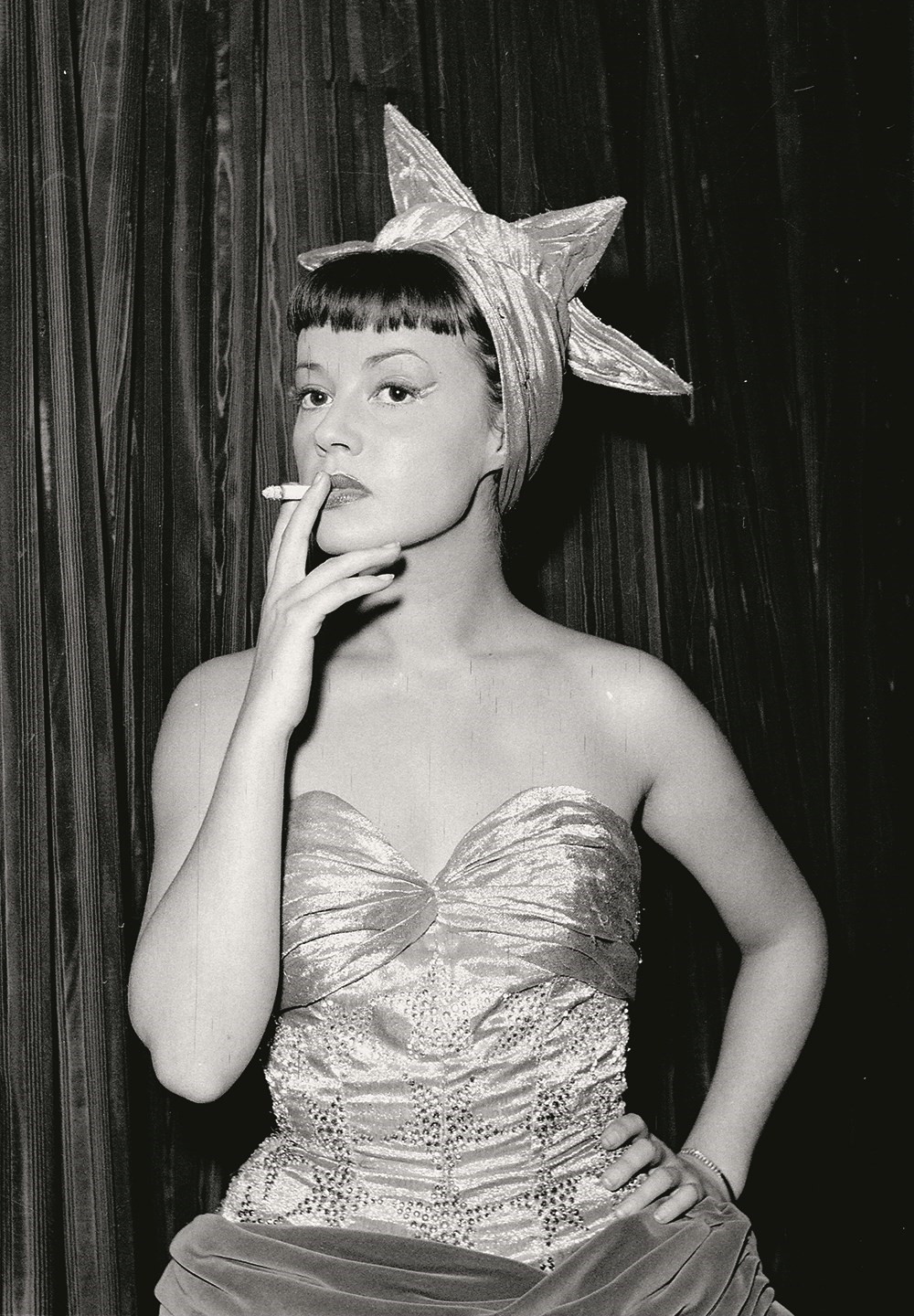

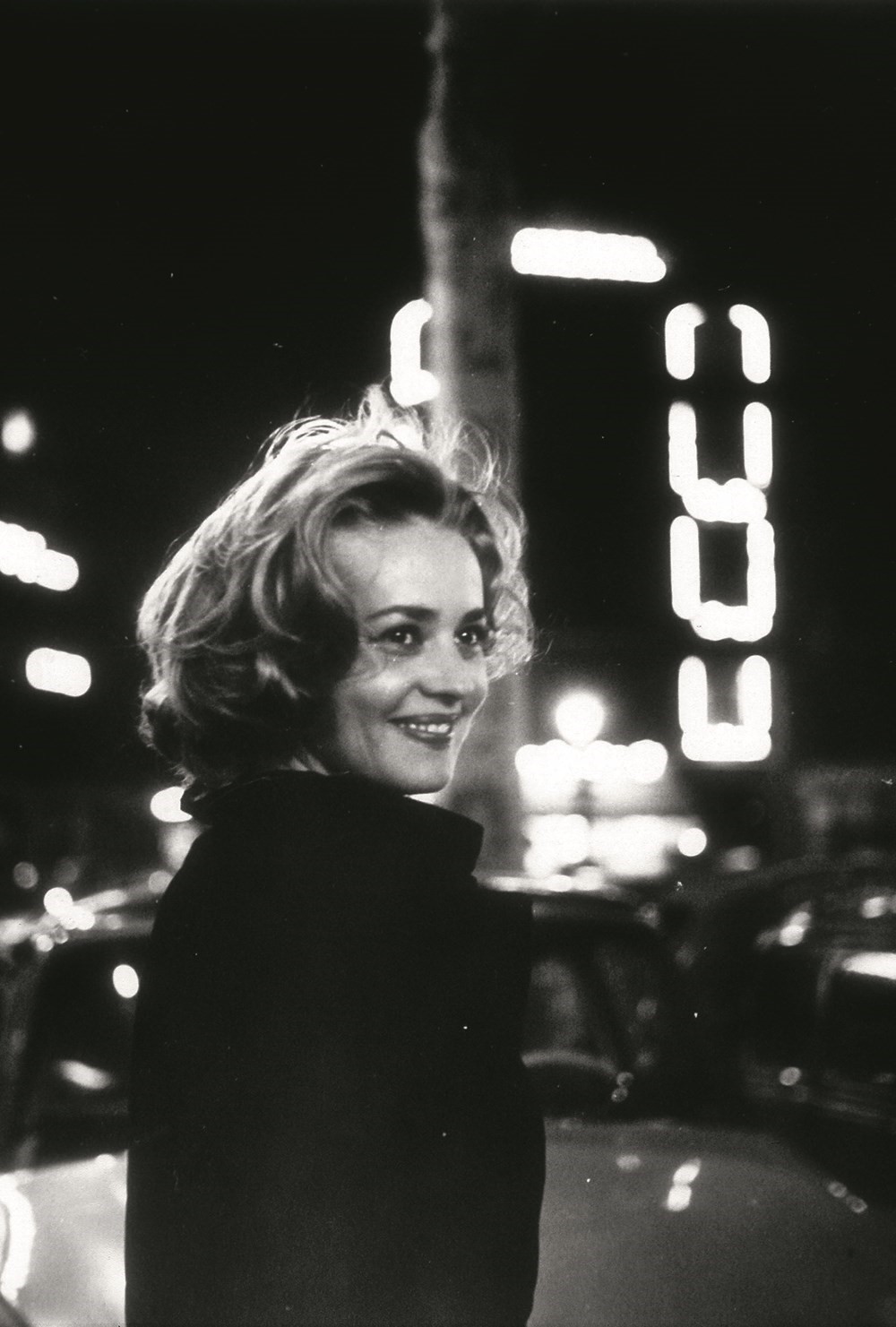

Jeanne Moreau is not only one of the great actresses of our time, she’s also a larger than life persona – a cult figure, and a heroine. She has worked with some of the most legendary movie directors of the 20th century: Welles, Cocteau, Antonioni, Buñuel, Fassbinder and of course had a close collaboration with François Truffaut. I first encountered her when I moved to Paris and met the actor Melvil Poupaud. In 2007, he starred in the François Ozon movie, Le Temps qui Reste, about a fashion photographer who dies very young, and Jeanne Moreau played the grandmother. Melvil put us in touch and Jeanne and I started to talk quite frequently on the phone, but we never found the time for an interview, because she’s so busy. She has her work as an actress, in both theatre and the movies, and her work with young filmmakers, as the artistic director and founder of the Angers Workshops. Then she also has a singing career – Jeanne is so pro-active, that for two or three years it was impossible to find a time when we could both meet. I finally sat down with Jeanne Moreau at the Brasserie Wepler in Place de Clichy, a local restaurant near her home in Paris, on the occasion of Francesco Vezzoli’s 24 hour project with Prada.

It’s a fascinating interview because she not only talks about the films she has done, but she says that for an actress, the films that one decides not to do are just as important. It was a mesmerising experience to meet Jeanne, and find her so young in spirit. Jeanne is forever young. She is not sentimental. She always looks forward to the future, yet she has encountered some of the great human beings of the 20th century. Ingmar Bergman, Anaïs Nin, Jean Genet, Henry Miller amongst countless others. As well as being one of the most celebrated actresses of our time, she reads, sings, writes, reads… The world of Jeanne Moreau has many dimensions. It’s a little like superstring theory.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I wanted to begin with the beginning; Jean Anouilh was very important to you when you were getting started. How was it that you came to theatre via him?

Jeanne Moreau: Yes, it was through a play during the occupation. I wasn’t allowed to go out and I lied to my father, and my girlfriends from school brought me to see Anouilh’s Antigone at L’Atelier. It starred his wife at the time, Monelle Valentin, and it was a piece that galvanised me because it’s a young woman that says ‘no’. And that’s my personality. I refuse all conventionalities. She said ‘no’ to power. She was leftist. She resisted. Me, I was leftist. And so I thought, that’s it. Because I wanted to be a dancer like my mother, but when I saw that, I said, ‘I want to be on stage to affirm, to express things.’

HUO: So it was politics that brought you to theatre?

JM: We didn’t talk about politics at that time. We were in resistance because we were occupied at the time. We wanted the Germans to leave. It was people on the right who submitted themselves to Marshal Pétain.

HUO: And following the experience with Anouilh?

JM: Well, I took theatre lessons and I was accepted at the conservatory and debuted at the Comédie-Française. I signed my contract on the day of my 20th birthday. The first piece that I played was the Tourgueniev piece Un Mois à la Campagne.

“Anouilh’s Antigone galvanised me because it’s a young woman that says ‘no’. That’s my personality. I refuse all conventionalities” – Jeanne Moreau

HUO: Was there a hero or heroine that inspired you?

JM: No, I was not allowed to go to the theatre, I was not allowed to go to the cinema. It wasn’t encouraged. My mother was a dancer at the Folies Bergère. She was in a Bergère dance troupe, Les Girls, which still exists. So I signed a four-year contract with the Comédie-Française. I performed in 24 shows in four years. I played everything you can imagine, Molière, tragedies, comedies. And they offered me a sociétaire contract. But I must not forget to mention that I debuted at the theatre before Comédie-Française, with Jean Vilar at the first Avignon Festival in 1947. Then Gérard Philipe invited me to come in 1952 but I was under contract with Comédie-Française. I had some very nice roles, which I gave to my girlfriends. I pretended I had a throat infection and went to Avignon Festival. And then I was sued. They were seeking ridiculous amounts of money. I was defended by a young Robert Badinter. You’ve heard of him I’m sure. He’s a famous lawyer. It’s thanks to him we ended the guillotine in France.

HUO: He defended you?

JM: Yes, and he wanted no money. My father knew nothing of my life. He learned of it from friends at the brasserie. I was the most popular person. I was very successful, the newspapers wrote about me, that’s when I met Tony [Richardson], that’s when I met Orson Welles who wanted me to play in one of his films. I was immediately offered roles that I accepted. One was with the male star of the time, Guy Marchand, who was a homewrecker. And then I played with Fernandel, with Gaba and then I was offered a part in a Tennessee Williams piece... Louis Malle, who’d never made a film, came to see me in it, and that’s when he asked me to work with him. So I learned everything from cinema, not theatre. But at that time filmmakers went to the theatre.

HUO: The first time you were swept up in it, was it the excitement that it would change what was happening in France?

JM: Of course. I was making a great deal of money, I didn’t need to think twice, I said ‘Mister, I like the script.’ I respected him a great deal at the time.

HUO: You’ve often said in your interviews that there was a sort of chemistry with Malle.

JM: Yes, we fell in love with one another, we had an intimate relationship for several years. We were separated, he married twice, we kept ties up until the end, before he disappeared.

HUO: And out of all of your films, which one was your favourite?

JM: You can’t choose. There are some that were tougher to make than others, Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud and Les Amants. It shocked everyone because we were making love. It was banned in Canada. I felt it was the end. A very painful film to make, very painful. And Viva Maria! I told Brigitte Bardot I was in quarantine.

HUO: With all your work there’s a strong notion of liberty…

JM: Yes, but with the feelings we had, I felt there would be a rupture. And then with Louis I met Truffaut. He hadn’t yet made Les Quatre Cents Coups. We crossed paths in a corridor, Louis introduced me and then went on ahead and François said, ‘Where can I meet you? I need to see you again.’ That’s when I first started seeing François. He took my number and we would meet once a week, at a restaurant that no longer exists on the Rue Marmont.

HUO: You said to me once, that the roles you don’t play are as important as the roles you accept.

JM: The roles I didn’t take I do not regret. The American film where he sleeps with the mother and daughter, with Dustin Hoffman…

HUO: You turned down Mrs. Robinson?

JM: I was shocked by the idea… it’s stupid isn’t it? And I was offered the role of the mean nurse in a nuthouse, with Jack Nicholson.

HUO: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Are there other films you turned down?

JM: I turned down Spartacus.

HUO: Why?

JM: The guy was sleeping with everyone, what’s his name? His son became a star too.

HUO: Kirk Douglas. So you said no to Kubrick?

“JM: The roles I didn’t take I do not regret. The American film where he sleeps with the mother and daughter, with Dustin Hoffman… HUO: You turned down Mrs. Robinson?”

JM: It wasn’t Kubrick who asked me. If it had been him, it would’ve interested me. But I said, ‘Who on earth is this guy?’

HUO: It’s always the filmmaker directly in conversation with you. It’s not through an agent, it’s not the industry. Do you have any projects that are unrealised?

JM: No. I just finished working with the oldest director in the world, Manoel de Oliveira. We filmed the movie in Paris and it will surely go to Cannes. It’s marvellous. It’s a magnificent story. Manoel was extraordinary. I think he is 105 years old.

HUO: I know two people that old and in good shape. Him and Oscar Niemeyer, the architect. A year ago you told me how you were working on something with Jean Genet’s Le Condamné à Mort?

JM: With Étienne Daho. And we’ll resume next year. I really admire Étienne Daho, and I found out that he was coming to the Olympia, and he sings one of the songs from Condamné à Mort. I was on my feet, I was dancing with everybody, and when Sur Mon Cou came on there was a calmness in the room, such marvellous emotion and I was overwhelmed. I found him backstage, I was with Claude-Eric Poiroux, who was the president of the Angers festival. I saw Étienne and said, ‘Listen, I have an idea, what if we did Le Condamné à Mort together? You knew Jean, you loved him, let’s do Le Condamné à Mort.’ It took us two years to put everything in place. We went to Canada, it was a triumph, we put a young rock band behind us, a stadium of a thousand people on their feet. We went to Belgium, to Italy, Lyon, and we returned to play Pleyel in Paris. They’re making a record now. I’m doing a record with Les Têtes Raides and I have two shows at the Avignon Festival this year. And next year we’re going to re-do Le Condamné à Mort.

HUO: And you’ve also said in an interview that for your work with Jean Genet, you didn’t have to learn anything about homosexuality because actually we’re all half masculine, half feminine.

JM: Well, to me it’s not a taboo to be homosexual! Of course we’re all masculine and feminine. And the more years go by, the more for a woman – certainly in my case I feel it – femininity gives way to virility. I have an authority that I’ve earned over the years.

HUO: Can you tell me about those meetings with Jean Genet?

JM: Yes I knew him. I starred in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and he’d come and get me at the theatre, we’d go on walks, go to parties, he’d flirt – he’d use me to pick people up.

HUO: Was it through theatre that you met?

JM: No. I met him through Florence Malraux who was good friends with people who were close to Jean, like Juan Goytisolo.

HUO: Another big writer.

JM: Yes, a Spanish writer, who now lives in Morocco. Florence Malraux was the turning point in my life.

HUO: She created connections for you?

JM: No, no she didn’t think that way, but she’s a woman with integrity, she is very important to me. And I hope to die before her, I couldn’t live without her.

HUO: So you could say she’s one of your very best friends?

JM: The closest. The only one.

HUO: What’s interesting also is your connection to literature.

JM: Truffaut was a big reader, all the directors I knew. Godard, Chabrol, they fed on reading, on literature. And since I wasn’t allowed to read as a child…When a child is told something isn’t allowed, what do they do? They read! I was ten years old when I read La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret. It gave me the fever. First I discovered the relationship between a priest and a woman, he got her pregnant. My paternal grandmother was a practicing Catholic. And on top of that I was discovering that while the Church, with a capital C, found out that l’Abbé Mouret impregnated this young woman, they condemned this young woman and saved the priest. I’ll never forget the garden where it happened. I understood what fiction was, because I spent summers in Auvergne, and I knew flowers and trees very well. And in La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret, there’s a garden in which all the seasons are mixed together at the same time. There were lilies at the same time as roses, everything was all mixed up! There were leaves dropping that were coppery even though there were plants sprouting… So I said to myself, ‘That’s fiction’: it was a symbol, every season of the year, every season of life was mixed up, and that sprout was showing me desire, but I knew nothing about desire.

HUO: And did you not use that idea yourself when you directed for the first time? That magnificent garden?

JM: Yes it was at my home. My first film, Lumière, was shot at my property, in Le Preverger near St. Tropez. I told myself then, ‘We’ll use symbols.’ Because I am a complete autodidact, I left after high school.

“All the directors I knew, Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, fed on literature. I wasn’t allowed to read as a child... when a child is told something isn’t allowed, what do they do? They read!”

HUO: The connection to literature is strong in your work because there was not only Genet but also Henry Miller, there was Jean Cocteau, there were many…

JM: But of course I knew Jean Cocteau well! We worked together on La Machine Infernale. And it was thanks to Jean that I met Jean Renoir, because I had dinner with Jeannot and Ingrid Bergman, who were going to film with Jean Renoir.

HUO: And with Jean Cocteau, was there an intense dialogue with him?

JM: Oh, there was an imbecile, a secretary that destroyed my letters from Cocteau…

HUO: No!

JM: All the letters, everything.

HUO: And Henry Miller?

JM: Well, Henry Miller I met through Anaïs Nin, because there was a young filmmaker and producer from Quebec who wanted to make a film out of one of Anaïs Nin’s novels that contacted me, and said ‘if you accept, I’ll get permission from Anaïs Nin’. I said to him, ‘You must come to Paris, I have to get to know you first.’ So here arrives a young brunette who declares her passion for my work and for Anaïs Nin, and she had a meeting with Anaïs Nin who was passing through Paris to promote one of her books. And we found ourselves in a hotel at Quai de Monet, rue Sebastien Bottin… I’d always wanted to live there. The film was never made but we met, got on well and became interested in each other. She spoke a lot of Henry Miller. One time Henry Miller was in town, and we met up and had dinner at the Ritz, and afterwards I went to film in the US, in Hollywood. There was a postman who wanted to marry me there, it was a big drama, an American postman. It was the same year Polanski’s young wife was assassinated. I arrived with my governess, thankfully she didn’t understand English, she would turn the TV on but she didn’t understand a word. She’d tell me about it and I’d say, ‘No, it’s just a TV series.’ And, it’s too complicated to explain, but I had French wines of an exceptional quality that a friend had sent me. And she’d prepare my meal before I arrived. My agent at the time who became a big producer, Mike Medavoy, had rented me a house in this block where all the stars lived and where you couldn’t come in unless you proved your credentials. Anaïs came because she had two husbands, she had an older one in New York and a younger one in Los Angeles, he was an alcoholic. Anyway one day she got me really worked up, she said, ‘I hope you don’t say you’re friends with us!’ I said, ‘Oh no, no I don’t speak of you,’ and she said, ‘Ah, because your reputation in LA is wrecked if you say you’re friends with playwrights.’

HUO: Something I wanted to mention, you’ve worked with these extraordinary directors that we’ve mentioned: there’s Truffaut, there’s Louis Malle and Manoel de Oliveira that are from the same generation, and you work with much younger directors, François Ozon and Amos Gitai. What’s it like to work with young filmmakers?

JM: It changes nothing! With Amos Gitai it’s much more tense, we really battled one another a lot. It was a long time before I worked on one of his films. I asked him for a script and he said ‘OK, you tell me the story.’ He said just that. I said ‘Well no, I’m not doing it.’ He contacted my agent at the time, he phoned me to insult me and we found ourselves at the Cinematheque not long after he’d mounted an exhibition and an homage to Pedro Almodóvar. I was there because I really like Almodóvar, I’ve always dreamed of doing a film with him. And I arrived, and he sees me, and I fell into his arms! I had no reason, he had insulted me! But I like his face, I really like his films and that’s how we worked together. But we fought...

HUO: And with Ozon there was that extraordinary film featuring you and Melvil Poupaud.

JM: Yes, but I was an admirer of Ozon from the start. He has creativity, he’s extremely different, like Truffaut. He alternates between films that are hugely successful and films that are experimental…

HUO: And what is your next film?

JM: It’s with a young director called Sandrine Veysset that was produced by the producer who committed suicide.

HUO: Humbert Balsan.

JM: Yes, he committed suicide a few years ago and he was her producer. And she obtained an advance and we’re not sure if we’ll be filming this summer. I’ll be filming a TV series with Josée Dayan. I’ve known Josée Dayan for 16 years and we made a very, very beautiful film together in which I interpret Marguerite Duras, and we have a project that’s being written, and a new film for the cinema.

Jeanne Moreau was born on January 23, 1928 and passed away on July 31, 2017 in Paris. This story first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2012 edition of AnOther Magazine.