As a Berlin exhibition opens celebrating the life and work of Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller, we remember five of his most groundbreaking films

Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller has lensed some of the most innovative, visually enticing films of the last half century, from Wim Wenders’ inimitable on-the-road adventures Alice in the Cities and Paris, Texas, to Jim Jarmusch’s ingenious odes to American misfits Down by Law and Dead Man. Coming of age in the 1960s, and inspired by the naturalistic methods of shooting pioneered by the burgeoning Italian neorealist, Nouvelle Vague and Cinéma Vérité movements, Müller set out to develop an esoteric manner of filming, which shunned unnecessary technical aids, fancy “camera acrobatics” and generic framing devices in favour of long, wide shots that suck viewers into the action with a magnetic intensity. He also determined to master the use of non-artificial lighting, aided by the new developments in film stock, and did so with all the skill of a painter, using specific colours to denote certain emotions.

Throughout his career Müller has sought out like-minded souls with which to collaborate – including Lars von Trier and Steve McQueen, alongside Wenders and Jarmusch – all of whom have declared themselves indebted to his remarkable vision and unwavering knowledge of his craft. “Robby would teach me things like, it says in the script that it’s a sunny day, but then on the day of the shoot it would be cloudy and about to rain,” Jarmusch once said. “Most people would just say, OK, let’s not shoot today. Robby would always say, let’s think, maybe the clouds and the rain is better, let’s not be closed off, let’s be open to what we might do.” Now, an exhibition at Berlin’s Museum für Film und Fernsehen, newly transferred from the Eye museum in Amsterdam, pays homage to the great cinematographer’s extraordinary life and work, spanning home movies from his personal archives, thousands of Polaroid photographs captured while on set, as well as various writings and interview footage that shed light on his practice. To celebrate, we look back at five of his most brilliant achievements.

1. The Left-Handed Woman (1977)

Müller met German author and screenwriter Peter Handke through Wim Wenders, for whom Handke had scripted the 1975 film Wrong Move, and was brought on board for Handke’s exquisite directing debut The Left-Handed Woman. It is the story of Marianne, a German housewife disenchanted by her comfortable suburban existence with her husband and son on the outskirts of Paris. One day, seemingly unprompted, Marianne demands that her husband leave her, and, left at home with their child, embarks on a journey of self-discovery, both lonely and empowering. Everything about Müller’s cinematography is breathtakingly beautiful and evocative. As The New Yorker critic Richard Brody notes, “the suburban landscape vibrates with the gusty rush of trains, a fireplace gives off palpable heat, and the springtime light seems painted on the screen by an artist’s hand”. Unlike his work with Wenders – defined by expansive, languorous shots, often captured from moving vehicles, and bright, beguiling colours – Müller here employs tight framing, motionless camerawork, and a soft, washed-out colour palette, all of which serve to emphasise the sense of isolation engulfing the film’s protagonist.

2. Paris, Texas (1984)

From 1972 to 1977, Müller and Wenders shot five films together, including Wenders’ iconic road trip trilogy, and the sublimely shot noir drama The American Friend, a visual homage to the paintings of Edward Hopper. The duo then took a seven-year hiatus from their ongoing collaboration before uniting for what is arguably their greatest masterpiece, 1984’s Paris, Texas. The film begins with an epic shot, captured by helicopter, which sees a dishevelled Harry Dean Stanton wandering desolately through a seemingly never-ending desert. Our protagonist, we find out, has been missing for some years, but discovers a new sense of purpose upon reuniting with his estranged young son, thereafter embarking on a road trip – son in tow – to find the boy’s mother. Wenders and Müller made the heart-wrenching film chronologically, with no pre-defined plan. They worked in complete harmony with the natural landscape, embracing blazing sunlight and torrential downpours alike, often shooting on the move, and the resulting atmosphere makes for uniquely immersive viewing. One of the film’s most famous scenes takes place in a peepshow booth, featuring a mesmerising Nastassja Kinski in a bright pink mohair sweater, and the ingenious employment of a one-way mirror, which Müller insisted must be real to achieve a genuine effect on-screen.

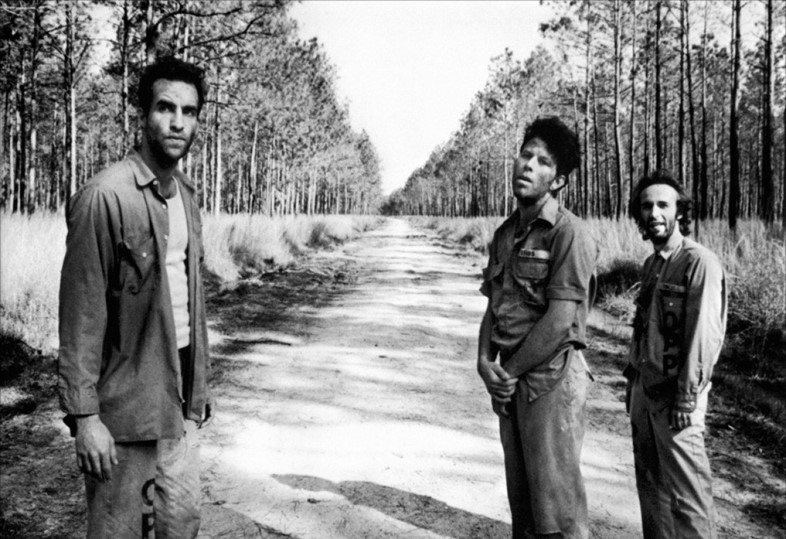

3. Down by Law (1986)

When Müller encountered Jim Jarmusch it was an instant meeting of minds: both creatives are fiercely independent and disdainful of studio methods of filmmaking. Jarmusch was instantly struck by Müller’s naturalistic mode of cinematography – from his 360-degree approach to lighting, framing and movement to his quest for authenticity of atmosphere – a perfect complement to the American auteur’s famously observational directing style. 1986’s Down By Law was the pair’s first collaboration: the tale of an out-of-work DJ, a pimp and an Italian tourist who stage a jailbreak from a New Orleans prison. Visually, the film is exceptional. Müller and Jarmusch opted to shoot in black and white, noting that the vibrant hues of the location’s landscape – comprising verdant forests and marshy swamps – would distract from the narrative impact, and it’s hard to imagine it any other way. The leading performances take centre-stage in the “neo-Beat noir comedy” (as Jarmusch terms it), cleverly aided by Müller’s masterful camerawork, which lends crippling claustrophobia to the scenes set in the miniscule prison cell, while miraculously skimming stretches of water and winding woodland paths to bring the trio’s escape to life.

4. Barfly (1987)

For his 1987 film Barfly – based on Charles Bukowski’s semi-autobiographical screenplay and starring Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway – French-Swiss director Barbet Schroeder enlisted Müller to work his magic on a movie largely set in dimly lit bars. Suffice to say the cinematographer rose to the occasion with remarkable aplomb, devising a special form of TL lamp with adjustable light intensity that could be easily attached to surrounding scenery and which infused the bar scenes with a painterly iridescence. Rourke is magnificent as Bukowski’s alter ego Henry Chinaski, a man who finds purpose in poetry and alcohol. We follow our down-and-out antihero as he drinks heavily, jabbers intellectually, engages in bar fights and falls under the spell of fellow alcoholic Wanda (Dunaway). Schroeder’s intention was to honour the free-flowing rhythm of Bukowski’s script, and Müller proves the perfect co-pilot, deftly translating the writer’s Romantic ramblings to the silver screen.

5. Breaking the Waves (1996)

Müller embarked on a new challenge in 1996 when he was approached by Lars von Trier to shoot his radically documentary-style movie Breaking the Waves. Von Trier had recently co-founded the Danish film movement Dogma 95, the manifesto for which ruled that all movies be shot with a handheld camera, use natural lighting and shun scenes conceived specifically for the camera. As such, Von Trier specified that Müller should not know the film’s plotline in advance and requested that the camera move all around the actors unconstricted, so that the cinematographer could play the role of unsuspecting observer, unable to set up certain angles or plan his use of lighting in advance. “He asked me to simply be a spectator and look wherever I wanted. The camera itself was not to have a judging function, but was to function like the eye of a child.”

The resulting film is radical on many levels. It follows a young, deeply religious Scottish woman who falls for a Norwegian oil rig-worker in her small coastal town. When he suffers from a life-altering injury, however, he encourages his lover to seek sexual satisfaction from other men – a quest she comes to view as God’s will. This alone had puritanical viewers up in arms, while DoPs around the world fumed at Müller’s intentionally unfocused imagery, defined by graininess, faded colours and unsteady camera movements. Today, however, it is widely hailed as a groundbreaking moment in cinematic history.

Robby Müller: Master of Light is at Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin until November 5, 2017.