As the world waits to see if she will become the first Green president, we revisit the wisdom of Brazilian environmentalist and politician Marina Silva

Back in 2012, for the S/S13 issue of AnOther Magazine, Vincent Bevans spoke to the charismatic environmental activist and politician Marina Silva about her hopes and fears for the future of Brazil and the world. Faced with the opposition both of her government and powerful financial forces within Brazil, she was a lonely voice arguing for change and a commitment to finding solutions to the crisis humanity's greed and laziness is wreaking upon the world. Bevans wrote then, "few think at this point that Marina will ever take the presidency of Brazil", yet two years on, as voters prepare for Sunday's election, she is favourite to do exactly that – poised on the brink of becoming the world's first Green president. With history in the process of being made, we revisit her inspiring and revolutionary words.

Most of the world became acquainted with Marina Silva during the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games in London, as she walked, serene and beautiful, slowly around the track, carrying the flag for her native Brazil and for the cause of global environmentalism. With her obvious benevolent spirituality and roots in the Amazon jungle, this UN-recognised Champion of the Earth seemed to represent everything the organisers wanted to say. But what few outside of Brazil know is that there, the decision to include her came as a surprise, and was vocally and angrily opposed by powerful groups, including in some surprisingly respectable circles. That’s because after rising from poverty to a position of fame and influence, she has chosen to be a constant, aggressive critic of those in power, rather than to collaborate. This has infuriated to no end the men who run Brazil – and not just its powerful conservative landowners, either. After achieving much as Minister of the Environment in one of Brazil’s most popular governments in history, she decided to resign from the cabinet of leftwing president Lula da Silva after she felt her goals were being ignored in favour of more reactionary forces in the country. Then she ran against his party for President.

"This planet is our home, and has taken care of us for millions of years. And we’re turning it into a hostile place” — Marina Silva

“We are living through a crisis of our very civilisation, a crisis that is itself made up of several crises,” she says. “There’s the environmental crisis – we are on track to lose 1,000 times more biodiversity than we did in the last 50 years. There’s a social crisis – two billion people living on less than two dollars a day, and soon we’ll have two more billion people on the planet. There’s a political crisis – the Arab Spring, the indignados, the failure of parties. And there’s an ethical crisis, obviously. This is not something that can be carried out by one party, one group, one person, or one country. It has to be the very force of humanity.” She gives Lula’s successful government its due, for lifting 40 million people out of poverty. But she has bigger goals at the moment. Few think at this point that Marina will ever take the presidency of Brazil, but she is running around the country, and the world, trying to organise a new type of cross-societal movement to deal with the crisis she speaks of.

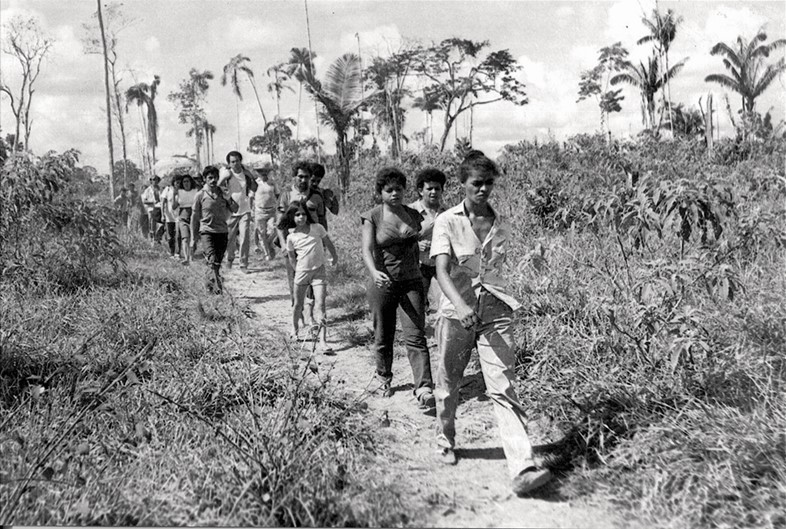

Marina is talking to me at a place that is quite far, both literally and figuratively, from her home in the Seringal area of the western Brazilian Amazon rainforest. We’re on a couch in the lobby of a budget airport hotel, in postapocalyptic São Paulo, the largest city in South America, wrought from concrete, inequality and broken dreams. She’s staying here another day before flying back to Brasília, then going home to the jungle. “Home is simply where you feel welcomed. But it shouldn’t take much imagination to realise that this planet is our home, and has taken care of us for millions of years,” she says. “And we’re turning it into a hostile place.” In a more personal sense, Marina’s home is still near where she was born, one of 11 children of mixed African-Portuguese ancestry to a family of traditional Amazon rubber farmers. Poverty and disease took her mother’s life while she was still young. “The jungle creates a paradoxical relationship. At the same time that it’s a source of infinite mystery, and a certain kind of grandiose fear, it also makes you feel so welcome,” she says. “We had everything we needed, and if we felt we needed to run or hide, we would go deeper into the forest.” Struck with poor health, Marina tried moving to the nearest city to live within the Church and work as a maid, and she eventually took with vigour to education, then to revolutionary socialism. In 1984, she founded a workers’ movement with close colleague Chico Mendes, who was assassinated a few years later for his environmental and social activities.

“In the past, one civilisation would fall and another one somewhere else would just rise up. But our civilisation, our problem, is fully global. If it goes down, that’s the whole world” — Marina Silva

After the country’s military dictatorship fell away, Marina quickly moved up the ranks of the newly-formed Workers’ Party and became Senator. When the party finally won the presidency for the first time, in 2002, she took her place in government and made big achievements in the reduction of the rate of deforestation. But starting before and since she left office, much of these gains have been reversed, most notably because of a new forestry code passed in 2012 that relaxes protection for the forest and forgives those who had simply ignored the past code, as many did. “Today we have two different, opposing models. One is quite viable, and involves increasing production by increasing productivity,” she says. “And we know these technologies work, as they are being used in some places now. We can double production without knocking down one tree. And then there is the other one, inspired by the old models of development, which expands agricultural production just by simply taking up more space. Eighty-four per cent of the Brazilian population was in favour of the first. Eighty per cent of legislators voted for the second.” The end of her term as Minister made the ways that the political system is forced to concede to moneyed interests painfully obvious. But it’s not only because of the huge size of Brazil that she believes her country has such an important opportunity and role to play in the environmental struggle. “Every country in the world has to find a way to come out of this test. But I think Brazil has all the conditions to find a new solution. We still have so many natural resources, we have the power to break this paradigm, to avoid committing the same errors that have already been committed in the US and Europe.”

A trained historian and psychoanalyst, Marina speaks using the erudite, carefully constructed phrasings of a left-wing academic, or even literary critic. She says she is stressing a new type of political engagement that is adequate to our times, a type of organisation she calls “authorial activism.” “If we can start from the idea that until recently, we had a kind of ‘managed activism’ – there were huge mobilisations but they were driven by an institutional or collective subject – a party, the academy, unions, and so on. That has changed progressively over the last 20 years. Through the internet and otherwise people have created ways of connecting with each other directly and coming up with their own questions and prospects, and have been able to democratise democracy itself. People don’t want to be spectators of their democracy. They want to be protagonists.” Of course, she says, all of this has risks: “We may end up simply atomised and ineffective. The big challenge is to find which kind of authorship can be found in the same space as the public interest.” This sounds hard. But the question is urgent, and we have no time to go slowly in accordance with everyone’s existing interests, nor can we completely break with the past. Do we have a chance of getting this done ourselves, or will we be victims of our own doing? “When I ask myself if I am an optimist, or a pessimist, I say that I am neither,” she says. “We need persistence, to find a base of ethical values that will allow us to give our own answer to the crisis we created.” It is for this reason that she established the Instituto Marina Silva, a non-profit sustainable development, education and advocacy centre in Brazil. “We don’t have a lot of experience solving crises of civilisation. In the past, one civilisation would fall and another one somewhere else would just rise up. But we don’t have that option. Our civilisation, our problem, is fully global. If it goes down, that’s the whole world.”

Text by Vincent Bevans