Doll’s houses have long been a source of intrigue and inspiration to a host of thinkers and artists. From Gulliver towering over the tiny homes of the Lilliputians to Alice dwarfing the home of the White Rabbit in Wonderland...

Doll’s houses have long been a source of intrigue and inspiration to some of our best-loved writers and artists. From Gulliver towering over the tiny homes of the Lilliputians to Alice dwarfing the home of the White Rabbit in Wonderland, doll-sized houses are a recurring motif in surreal narratives, a shrunken world for curious readers to explore and get lost in. Fashion’s love-affair with dolls and their accoutrements ranges from photographer Tim Walker pitting Lindsey Wixson against a terrifying outsize doll in a stately home for a 2011 Vogue Italia shoot, seen recently in an exhibition dedicated to the photographer's work at Somerset House; Viktor & Rolf staging part of their 2008 Barbican exhibition in a 6-metre high doll’s house; and a variety of designers creating bespoke clothing and accessories for Barbie when she recently turned the grand old age of 50. Doll’s houses appear in the work of artists such as Laurie Simmons, Andreas Slominski and Pipilotti Rist, and in animator Suzan Pitt’s weird and wonderful 1979 film “Asparagus,” while filmmaker Wes Anderson’s stylised sets, usually family homes, are often compared to doll’s houses.

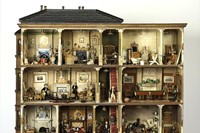

The vogue for miniature houses began in the 17th century, when aristocrats would build lavish models of their own homes as display cases for their wealth and taste; by the 19th century they began to be manufactured as children’s toys and as aids for teaching girls how to run a house, and by the 1950s were being mass-produced for baby boomers. Later, the market would be flooded with pink palaces for the likes of Barbie and Sindy, while the bizarre Sylvanian Families would take residence in a variety of twee abodes, including a windmill, a gypsy caravan and even a tree house. No longer a symbol for out-dated social mores (Ibsen titled his play about domestic entrapment in late-19th century Norway “A Doll’s House,” after all), progressive parents can now furnish their children’s rooms with “gender-neutral” doll’s houses.

"No longer a symbol for out-dated social mores...progressive parents can now furnish their children’s rooms with “gender-neutral” doll’s houses."

For Document in this season’s issue of AnOther Magazine, we reprinted art critic John Richardson’s essay on eccentric Manhattan hostess Carrie Stettheimer’s doll’s house – a treasure trove of mini-masterpieces by the likes of her artist friends Marcel Duchamp, Gaston Lachaise and William Zorach, and painstakingly hand-crafted furniture by Carrie herself. In his essay, entitled The Stettheimer Dollhouse, taken from the book Sacred Monsters, Sacred Masters, Richardson suggests that the house was something of a substitute for the spinster Carrie, who for years lived with her ailing mother and yearned for a place all her own. Once she moved out, she never touched the doll’s house again, and it was donated to the Museum of the City of New York after her death. It now houses a collection of figures modelled on the Stettheimers’s illustrious circle, a mini-snapshot of an exciting and bygone time. Meanwhile, the doll’s houses at the V&A Museum of Childhood in London provide a diminutive timeline for changing architectural tastes, moving from the rambling mansions of the 19th century to a Bauhaus-inspired modernist house. And the early 20th-century doll’s house at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, decorated every Christmas with miniature wreaths and baubles, is one of the museum’s most cherished exhibits.

Text by Laura Allsop