Ned Beauman discovers that he loves a monopoly, no matter how obscure

In the London Library this week, I came across an intriguing little book called The House of Gibbs and the Peruvian Guano Monopoly by WM Mathew. That title is notable not just for its unexpected euphony but also for its implication that once upon a time somebody genuinely made it his most cherished ambition to corner the market in sundried birdshit. But then perhaps that shouldn't be a surprise: absolutely anything will get you rich if you have all of it in the world, with the possible exception of time, and even that inspired a good song. The problem is that monopolies are awfully elusive creatures, as we can see from the struggles of the three men who died on this date – drug baron Pablo Escobar, financier Jay Gould, and circus impresario John Nicholas Ringling.

There isn't much in common between their methods. For the Ringling Brothers, it was nothing but diligence: beginning in the 1870s, they methodically built up their business with bank loans of as little as $20 a time, until finally, with their acquisition of the American Circus Corporation in 1929, they controlled every travelling circus in America. A young scruff who ran away to join a Ringling Brothers circus would have had a nasty shock: employees signed contracts with fifty-one rules of conduct which forbade them from such indulgences as playing musical instruments late at night or 'nodding to friends or acquaintances who might be in the audience', and they were policed by Pinkerton detectives. Not quite the usual romantic image of carnival folk.

Meanwhile, John Nicholas Ringling's image as a tireless self-made man was deliberately intended to recall America's Gilded Age industrialists, but when a real one of those, Jay Gould, lunged for a monopoly of his own, it was more a matter of cunning than hard work. The odd thing is that his attempt to corner the gold market had very little to do with gold itself: it was part of a ridiculously complicated scheme to increase the use of his railroads by stimulating wheat exports to Europe. Gouldfinger, as we should probably call him, used fifty or sixty different brokers just to conceal the magnitude of his bullion purchases, and on Black Friday, the day in 1869 when the plan began to unravel, transactions were going through the Gold Exchange at such a rate that telegraph wires literally melted.

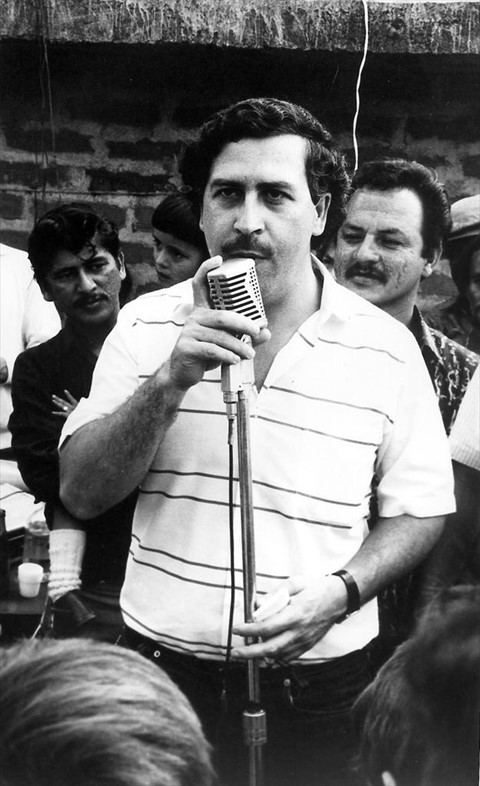

Pablo Escobar, finally, had neither exceptional diligence nor exceptional cunning. 'He wasn't an entrepreneur,' writes the journalist Mark Bowden, 'and he wasn't even an especially talented businessman. He was just ruthless.' By 1989, El Doctor had killed or intimidated so many people that he controlled more than half of all the cocaine shipped into the US, and had turned its production and trafficking into by far the biggest industry in Colombia. Curiosities in his mansion included a 30s-era sedan peppered with bullet holes that supposedly had belonged to Bonnie and Clyde, a full-scale gynaecological examination chair in the master bedroom, and some hippos.

The one thing that all monopolies might be expected to have in common is that once you have one in your sights, God himself couldn't persuade you to let it get away. True? Well, it's true of Ringling, Gould and Escobar (what a law firm that would be). But the funny thing about Antony Gibbs & Sons' guano monopoly is that after a few lucrative decades they just voluntarily gave it away and took up merchant banking instead. After that they prospered and were eventually bought up by HSBC in 1980. By contrast, Escobar was shot dead by soldiers, the Ringling dynasty disintegrated into bitter factions, and Gouldfinger ('pretty girl, beware of his heart of Goooouuuuld!') was left with a permanent mark of infamy for causing a financial panic. Perhaps the trick to a good monopoly is the same as the trick to a good death – the impossible art of letting go.

Ned Beauman used to be Commissioning Editor at Another Man, writes often for Dazed & Confused and has contributed to the Guardian, the Financial Times, and many other publications. His debut novel Boxer, Beetle will be published by Sceptre in August 2010.