As a new retrospective of her work opens at Tate Modern, we examine the enduring influence of Fahrelnissa Zeid

Who? Born into the Turkish elite and made an Iraqi princess by marriage, Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901-1991) went far beyond the anticipated role of a royal spouse and socialite. She was one of very few women who attended the Imperial School of Art in Istanbul at the beginning of the 20th century, and travelled extensively with her first husband, the literary figure Melih Devrim, in order to visit the greatest museums in Europe and study the works of Old Masters and the Renaissance. By 1933 she had entered her second marriage to Prince Emir Zeid Al-Hussein, and was introduced to Istanbul’s contemporary art scene by her step-son, an acclaimed art critic and newspaper columnist. This new exposure saw Zeid exhibit with the experimental d Group, but she never truly embraced their commitment to traditional Turkish aesthetics. After becoming frustrated by the lack of opportunities to show work, she launched an exhibition in her own apartment; a revolutionary idea for the time. Her display of 172 paintings was a huge success and established Zeid’s career as a formidable contemporary artist.

In 1946 Zeid moved to London with her husband, who had been appointed Iraqi Ambassador to the United Kingdom. She wasted no time fully immersing herself in the city’s contemporary art scene, and also made regular trips to Paris, where she showed her work at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles alongside leading abstractionists including Sonia Delaunay and Jean Arp, to great critical acclaim. Back in the UK she exhibited widely and threw lavish parties for the most revered artists, gallerists and critics of the day, earning herself the nickname ‘Painter Princess’.

As a woman of considerable privilege, nothing could prepare her for Iraq’s military coup in 1958. When the Hashemite royal family was assassinated Zeid and her husband were forced to vacate the embassy, and had to adjust to a much more meagre existence. Unperturbed, Zeid embraced her newly domestic lifestyle and infused her art with turkey and chicken bones – a tribute to her newfound skills as a cook.

In the last two decades of her life Zeid continued to pursue her art with zeal. Once widowed she moved to Amman, Jordan, in order to be close to her son, where she continued to work tirelessly and founded the Fahrelnissa Zeid Institute of Fine Arts, influencing a whole new generation of experimental artists in the process.

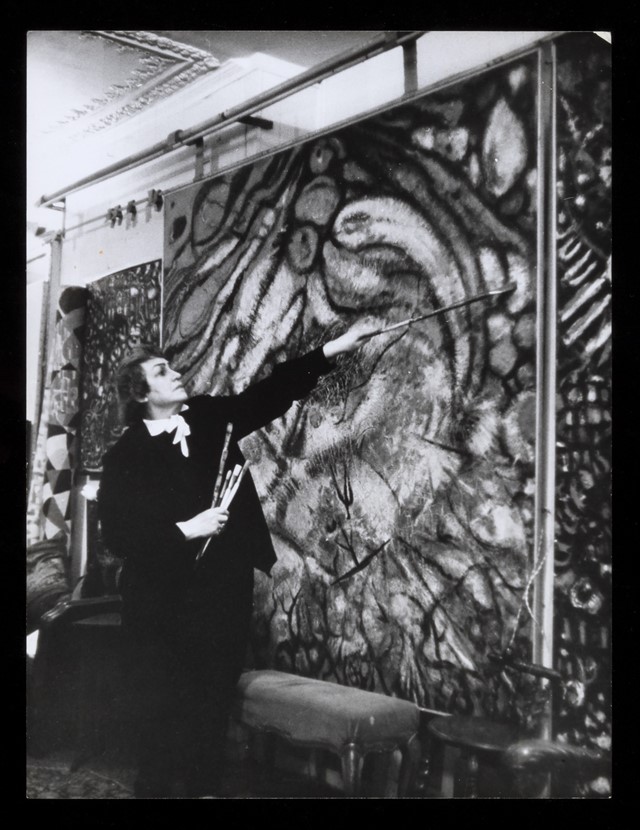

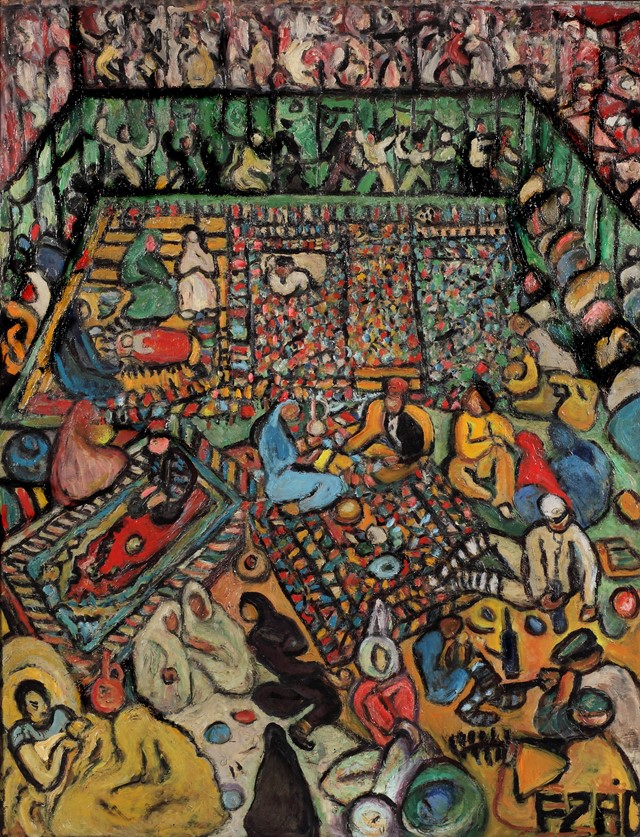

What? One particular aesthetic or art movement never defined Zeid. She was influenced as much by her Turkish heritage as she was by the works of Breughel, and was also informed by the principles of Fauvism, Cubism and Expressionism, which led to a lasting preoccupation with the power of colour. Her earlier paintings were luscious, figurative pieces inspired by her daily life, dreams and memories. By the mid-1940s her relationship with theories of Abstraction saw a sizeable shift in her work. She began creating enormous canvases that blended Byzantine motifs with contemporary, experimental patterns. In fact her works became so large that in some cases they barely fitted into the gallery. For her solo show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1954 her painting Towards a Sky had to be hung with a third of it rolled up, as the ceiling wasn’t high enough.

Although her abstract period is arguably her best-known, Zeid made a conscious return to figurative work in her later years. These stunning, stylised works often depicted close family or friends, as well as a particularly striking self-portrait, which shows the artist wearing a dramatic printed dress, enormous earrings and coquettish arched eyebrow.

Why? Zeid continuously defied convention throughout her life. In her youth she vehemently pursued an education rarely afforded to women at the time, and she refused to be defined by her role as a royal wife. Even in her artistic practice Zeid escaped classification. She borrowed from movements and aesthetics as she saw fit, and carved her own position among the art world of Istanbul, Paris, London and beyond. With her tenacious spirit, exceptional vision and remarkable eye for colour she challenged the status quo, and was instrumental in defining the principles of modernism.

Fahrelnissa Zeid runs from June 13 until October 8, 2017, at Tate Modern.