As a mammoth new exhibition of his work opens at London's Tate Britain, we examine a few lesser known facts about the prolific British artist

Born in Bradford, West Yorkshire in 1937, David Hockney has been relentlessly reinventing and evolving his practice ever since he won a scholarship to his local grammar school. This week, the best part of a century on, London’s Tate Britain opens its extensive survey of his work, criss-crossing between the big sky of California and the rolling hills of Yorkshire, comprising vivid paintings and hazy faxes; bare bums and sharp slacks. But a retrospective it is not: as he edges into his 80th year, Hockney is showing no sign of slowing down. “It’s always what I’m doing now,” he told The Guardian in 2015. “I don’t reflect too much. I live now. It’s always now.” To mark the show, here are ten things you might not know about this prolific artist.

1. He’s a sort of anarchist

Describing his politics, Hockney has previously defined his views as “a sort of anarchism that took from both the left and the right. Personal responsibility is sort of a rightwing thing that anarchists would support, and so do I. Looking after your neighbour is a leftwing thing, and again I would support that. Ultimately, I’m about liberty and I think you have to defend it.”

2. He’s a synesthete

Although not apparent in the abundance of his practice, Hockney was born with synesthesia, and he sees synesthetic colours in response to musical stimuli. He does however make use of it in his work, designing the stage sets for ballets and operas including The Rake’s Progress and Magic Flute, where he bases colours and lighting on tones and shades seen whilst listening to the productions.

3. He’s responsible for more than just lining the walls at the Royal College of Art

While studying at the Royal College of Art, Hockney refused to complete the essay requirement on the grounds that his work should be judged entirely on his art practice. The RCA withheld his diploma, and he retaliated by producing his own parody of the requisite, where he satirised the bureaucracy that weighed down the students. They changed their regulations, and he graduated with the gold medal in painting.

4. He’s an ardent supporter of living in the now

Henri Cartier-Bresson remarked at the age of 93, “It’s not longevity, it’s intensity that counts.” And Hockney – in spite of the fact that, like Cartier-Bresson, is already doing very well – agrees: “It’s a different attitude to time,” he told The Telegraph. “That’s what I have. We all get a lifetime. They’re different, but we all get one.” A defender of a person’s right to smoke, Hockney also asks: “Why is everything now geared to longevity? If everything’s directed at longevity, you’re denying life. There is only now.”

5. He regrets the death of Bohemia

While talking about the abandonment of the bohemian lifestyle, Hockney lamented to The Guardian: “Bohemia was against the suburbs, and now the suburbs have taken over. Bohemia is gone now. When people say ‘well wasn’t it amazing to be openly gay in 1960’, I point out, well, I lived in Bohemia, and Bohemia is a tolerant place. You can’t have a smoke-free Bohemia. You can’t have a drug-free Bohemia. You can’t have a drink-free Bohemia. Now they’re all worried about their fucking curtains, sniffing curtains for tobacco and stuff like that.”

6 ... And the irrelevance of the avant garde

Similarly, but under contrasting conditions, in his opinion “nobody takes any notice of the avant garde anymore”. He told The Spectator: “They’re finding they’ve lost their authority. They thought they would get authority by damaging the other, earlier establishment. But by doing that you damage all authority.”

7. He’s a loyal friend

Hockney has remained close with many of his former lovers, with whom his relationships simply evolve. Although uninterested in marriage or children, Hockney has maintained a working relationship with Gregory Evans for 40 years. “I’m not one to fall out with people, really. There are some people I don’t see, but it’s because they’re so boring.”

8. He is partially responsible for the thesis affirming the role of technological advances in art

In collaboration with physicist Charles M. Falco, Hockney defined the Hockney-Falco thesis, which affirms that advances in realism and accuracy in Western art since the Renaissance were the result of camera obscuras, camera lucidas and curved mirrors, rather than developments in technique or individual genius. The theory has been presented and argued in publications and at conferences around the world.

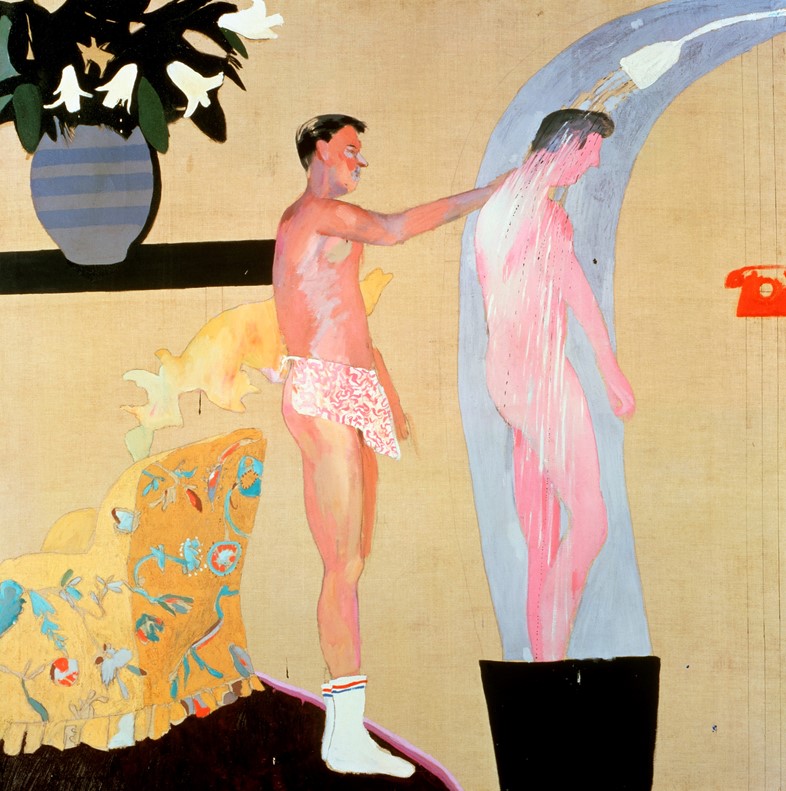

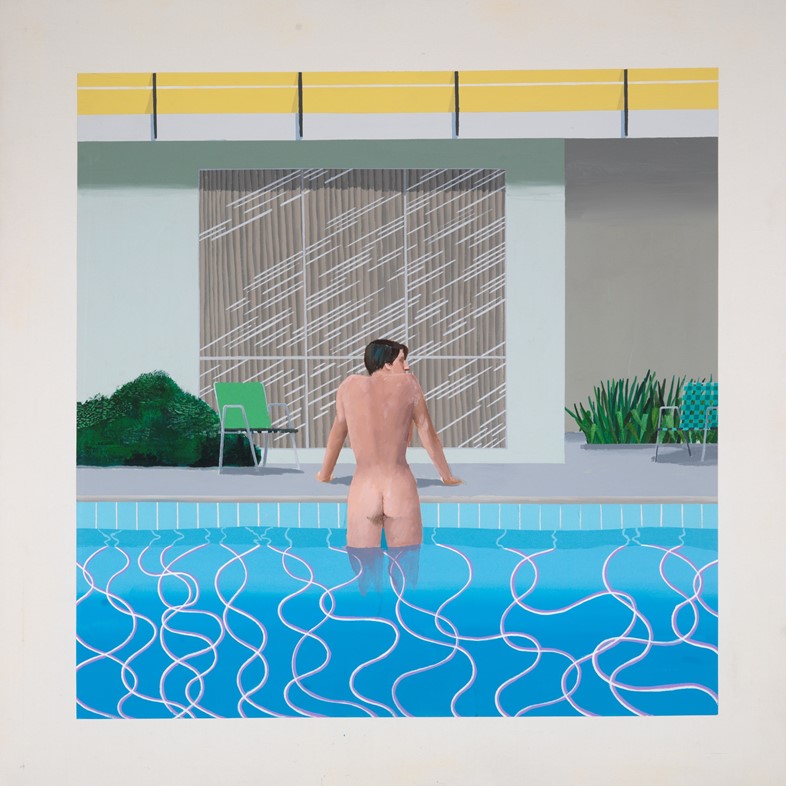

9. His fascination with pools is ongoing

Hockney’s most iconic piece, A Bigger Splash, whose enigmatic title and composition has inspired films, visual impersonations and the chasing of the L.A. sun, was in fact part of a series. The set of swimming pool pictures depicting the splash of foam after a dive also includes The Splash and A Little Splash; which in some ways removes from its poetic lyricism, and allows the piece to sit more comfortably within the context of Hockney’s dry wit.

10. He’s an optimist, in spite of everything

Despite his dry humour and natural disposition for pessimism, Hockney describes himself as an optimist. “Yes, in the end it’s no good being a pessimist. And I have a good laugh every day,” he told The Guardian. “You’ve got to. That’s what keeps you going. There’s loads of people who don’t laugh at all, you know.” He cites a Matisse exhibition he’d seen at the MoMA as a particular inspiration: “That show was unbelievable. It was pure joy. Pure joy. And joy is a great thing to give to people.”

David Hockney runs until May 29, 2017 at Tate Britain, London.