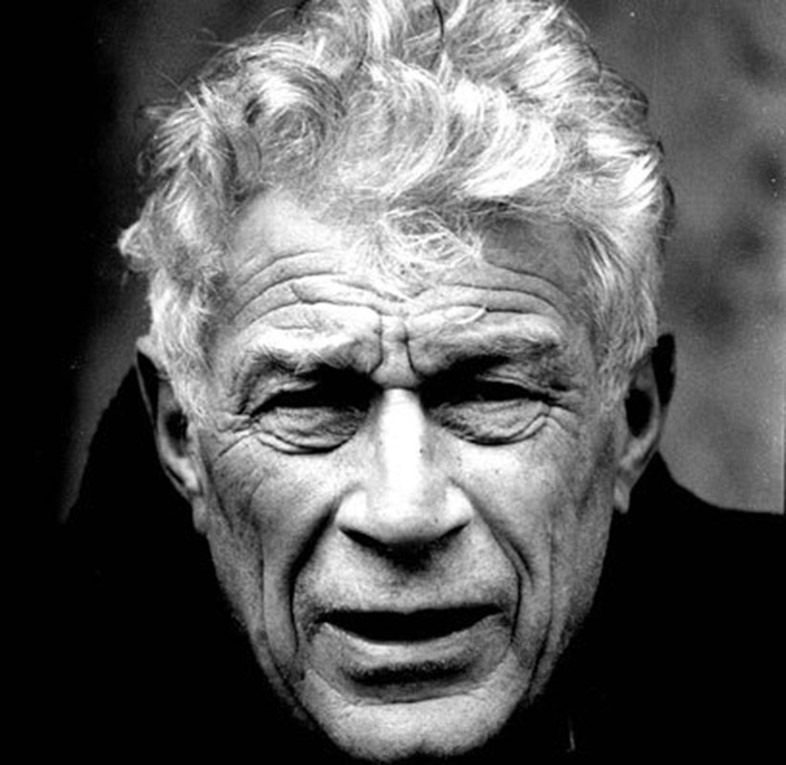

Following the sad news of the legendary art critic's passing, we reflect on the immutable legacy he leaves behind

Yesterday we lost John Berger, a man who believed in the compassionate, world-changing power of storytelling. His ideas, and the clarity with which he expressed them, changed how a generation looked at visual art. His nine decades combined headline encounters – painting lessons with Lucien Freud, dinner parties with Henri Cartier-Bresson, documentaries with Tilda Swinton – with social awareness and engagement.

Berger’s writing sings with the courage and curiosity of an always-open mind, his freewheeling prose is art in itself. He was a radical thinker and a believer in radical action, in protest, in getting involved. The timing of his departure feels cruel – as the world hunkers down into its fearful silos of iron-clad, opposing opinions, his inclusive, provocative, humorous voice is needed more than ever. As Tilda Swinton once told us, "The way in which Berger introduced my generation to the context(s) of art is invaluable, and his influence incalculable." Here are just three lessons that we have taken from his life and work.

1. Put your money where your mouth is

In 1972, Berger won the Booker Prize for G, a picaresque tale of a Casanova-like figure set against the turbulent years of the early 20th century. No one really remembers the book, but Berger’s acceptance speech was headline news. In it, he deconstructed the power of prizes and protest and, in recognition of the impact of prize sponsors Booker McConnell’s commercial activities on the poverty of the Caribbean, he donated half the prize money to the Black Panther movement. This move enraptured some, enraged others, but for Berger, “the sharing of the prize signifies that our aims are the same”. He was the enemy of complacency or simply symbolic gestures – his work pushed people to enact change through their own actions. “To protest is to refuse being reduced to a zero and to an enforced silence,” he said. “One protests… in order to save the present moment, whatever the future holds…"

2. There is power in paying attention

One of Berger’s most defining characteristics was his capacity for paying attention. "If I am a storyteller, it's because I listen,” Berger said. “Stories come to you all the time if you listen…" The stories he found often came from encounters with unexpected individuals – a country doctor of A Fortunate Man, the peasants alongside whom he lived for decades in the French Alps – which he converted into books that explored the biggest questions of life. In perhaps his most celebrated work, the book and TV series Ways of Seeing, he elucidated a new perspective on the experience of art, opening up an opaque world for the consumption and pleasure of a new audience. And even as the credits were rolling, he undercut his role of expert – exhorting viewers and readers not to take his ideas as gospel. “What I’ve shown, and what I’ve said… must be judged against your own experience”. He enacted complete freedom in his work, and advocated it for others.

3. Enjoy the small things

Berger became one of the most admired writers and art critics of his age, yet his life remained largely unchanged by fame and adulation. He tried to live in the present moment as “an escape from prescriptions, prophecies, consequences and causes,” and used the intense observation allowed by this practice to conjure worlds through quotidian details, and stories informed by immediate concerns. In a similar way, life’s small details gave him inordinate pleasure, defined in his description to the Paris Review of swimming in public pools. “As swimmers we share a kind of egalitarian anonymity. No shoes, no marks of rank, just our swimming costumes. If you accidentally touch another swimmer while passing him or her, you offer an apology. The limitless cruelty towards others like ourselves, the cruelty of which we are capable when we are regimented and indoctrinated, is difficult to imagine here.” Here, as in the rest of his life, the stories were in the details. And the pleasures were there too.