We explore the history and Viennese renaissance of this storied printing technique, as exemplified by masters from Albrecht Dürer to Carl Moll in a thrilling new tome

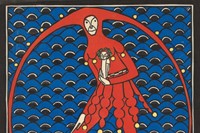

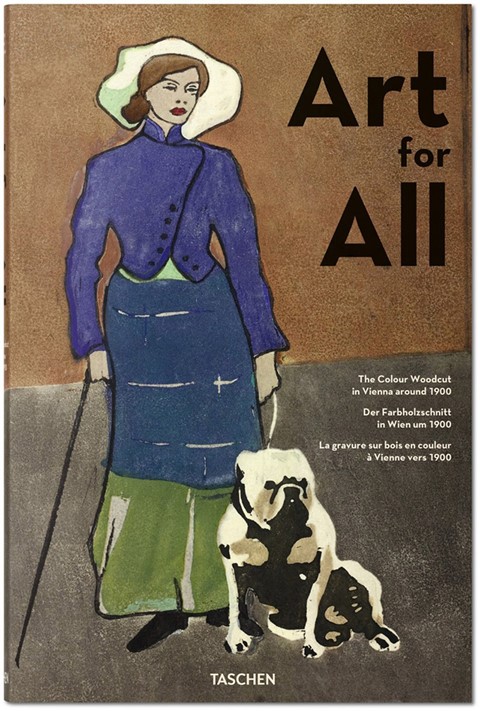

The woodcut is one of the oldest known printing techniques, achieved by carving an image into a block of wood with a gouge so that the printing parts are level with the block's surface while the non-printing parts are in relief. It was popularised in the Middle Ages, and reached its artistic culmination courtesy of master printmaker Albrecht Dürer. But in the centuries that followed, the woodcut was largely disregarded by artists, principally reserved for book and periodical illustration alone, and it wasn't until the early 20th century, when photography and modern printing techniques had rendered it redundant in that respect, that the art of woodcut printing began to recapture creative imaginations across Europe. One of the most fertile, and significant, cities in the woodcut renaissance was Vienna, where the technique was revived and embraced in brilliantly new and experimental ways. This "undreamt-of-heyday" however, has been largely overshadowed by Vienna's other, more famous artworks from this prolific period in the city's cultural history – a fact that a beautifully illustrated new tome from Taschen, titled Art For All and including the work of around 50 artists, is looking to alter.

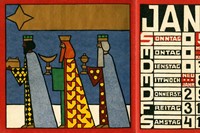

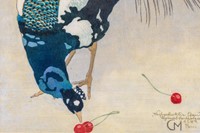

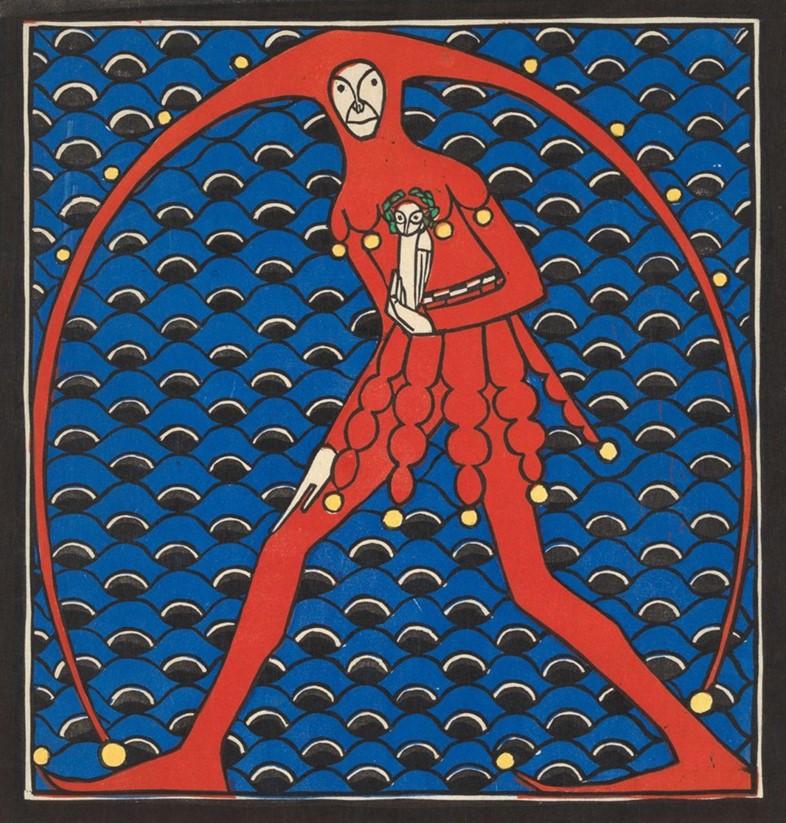

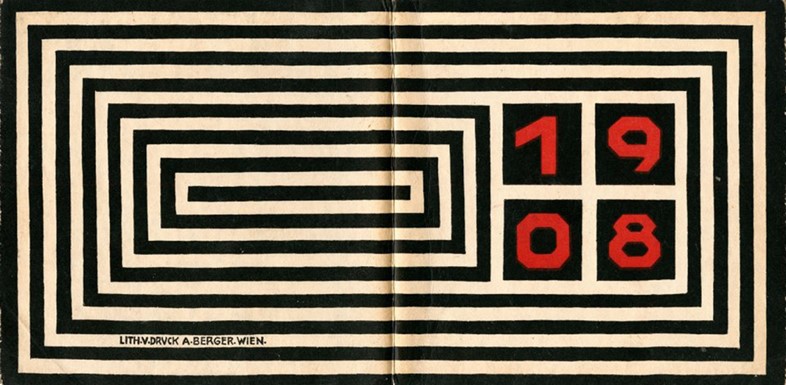

At the heart of the woodcut revival lay the Vienna Secession, the group founded by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil and various others in 1897 that would go on to define the city's new "artistic age". The group held a number of seminal exhibitions in their now-renowned exhibition building, designed specifically for the purpose in the city centre, placing particular focus on "the beauty of the line," as the book's co-author Tobias G. Natter explains. These displays provided "a prominent stage on which the woodcut was able to present itself in the early stages", sparking a widespread interest in the experimental potential of the medium. Before long, Natter elaborates, painters, graphic artists and craftsmen like Carl Moll, Emil Orlik, Kolomon Moser and a number of the students at the famed Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna's School of Applied Arts) were investigating the medium, conjuring up lively figurative and animal studies as well as verdant landscapes, in addition to creating innovative pattern-based and typographical works.

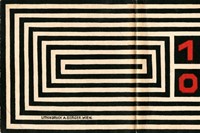

The aesthetic qualities the woodcut and its pioneers spawned – "exaggerated outline drawings, stylistation, a tendency towards areas of uniform colour, and austere geometric figures" – came to embody "the modern pictorial idiom at the beginning of the 20th century", a fact propogated by its easy reproduction. Indeed, it played a key role in the democratisation of art at the time, within the context of an 'Art for All' movement. "While a painting by Gustav Klimt was beyond the reach of most pockets," the book's foreword explains, "the woodcut now gave ordinary people the chance to purchase works of art." Perhaps this is why – although the Viennese woodcut zennith lasted just a decade, tailing off in 1910 – its influence was so broad-reaching, echoed in as diverse movements as expression and modernism.

Art for All: The Colour Woodcut in Vienna Around 1900 is out now, published by Taschen.