“The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the diary I let people read,” the American photographer once wrote. As her seminal work goes on display again at MoMA, we consider the themes at play within it

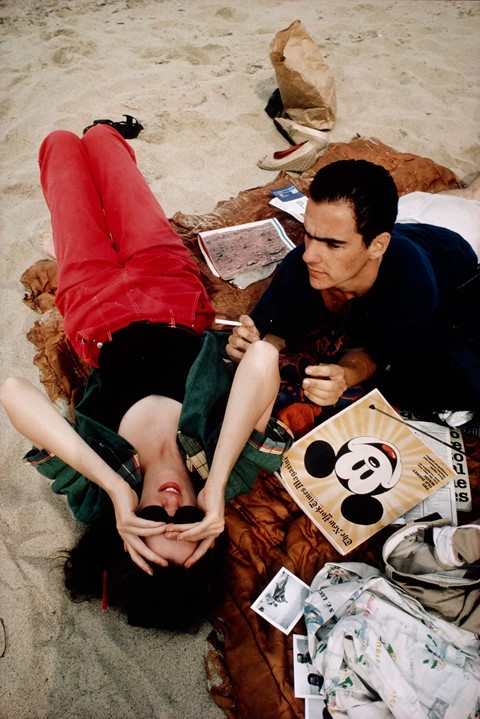

For American photographer Nan Goldin, photography has always been about capturing moments with complete honesty, revealing life as it was happening. “The camera was like an extension of my hand. I shot all day and never moved anything. For me, it was a sin to move a beer bottle out of the way because it had to be exactly what it was,” Goldin said in a 2013 interview about her impulse to photograph. Her 1980 image Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City, is a notable example of how Goldin was able to create an intimacy with her idiosyncratic mode of documentation, instilling in viewers an electric feeling of closeness – of being there in the scene.

It’s no surprise, then, to learn that her subjects were mostly friends, lovers and herself: friends tangled in each other’s bodies, lovers who may not have been good for one another and herself, battered by a lover. Unlike the traditional fine art photography aesthetic prevalent in the 1970s, Goldin’s visual language veered towards blurry, densely saturated images treading the line between crudely diaristic pictures and lush fashion photography. Although she got flak from male counterparts at the start of her career, because of this, Goldin’s candid work has since left a palpable impression on subsequent photographers, like Ryan McGinley, who also strive to unveil their lives with candour.

Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City is an image from Goldin’s ever-evolving photo narrative The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a compilation of deeply personal photographs going back to the late 1970s from the artist’s life in London, New York, Berlin and beyond. The seminal work, which was named after a song in The Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, is now on show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the form of a sequence of nearly 700 slides projected one-by-one set against a music soundtrack. For 43 minutes, portraits of love, light and ecstasy are interspersed with moments of pain, darkness and loss. The Ballad started as a slideshow art piece that Goldin showed in underground cinemas and clubs across Europe, beginning in 1983, and later became her first photo book, released in 1986. “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the diary I let people read,” Goldin later wrote about the piece. “The diary is my form of control over my life. It allows me to obsessively record every detail. It enables me to remember.”

“Real memory, which these pictures trigger, is an invocation of the color, smell, sound, and physical presence, the density and flavor of life” – Nan Goldin

While much of The Ballad is propelled by bleakness and longing – many of the friends she photographed died from AIDS very young – the collection also pulses with delight and desire, especially in the ardent images chronicling the pursuit for intimacy as well as the struggle between autonomy and dependency in relationships. Rise and Monty Kissing, New York City is a prime example of the latter. “Real memory, which these pictures trigger, is an invocation of the color, smell, sound, and physical presence, the density and flavor of life,” as she wrote.

One of the biggest influences on Goldin’s body of work has been Larry Clark’s controversial book titled Tulsa (1971), a collection of black-and-white photographs depicting youth from Oklahoma having sex, shooting up and meddling with guns. Like Clark, Goldin seems to be enamored by lives straying from convention, and scenes of lawlessness. Or, by the desire to show life just as it is. As she once surmised: “It was not about the wild times. I never thought they would end. I was living in the moment, not documenting for the future.”

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency runs until February 12, 2017 at The Museum of Modern Art in New York.