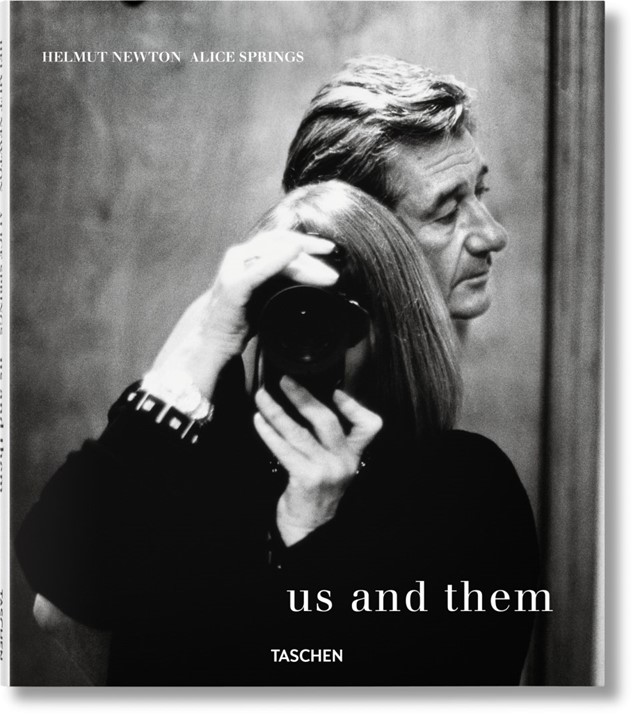

Us and Them, republished this month by Taschen, is a powerful ode to the relationship that shaped two of the 20th century's most important creative talents

There is one very well known photograph by Helmut Newton, taken in 1981 and somewhat impersonally titled Self-Portrait with Wife and Model, which neatly distills the powerful and enduring relationship between he and Alice Springs, to whom he was married for more than 50 years. In it, a nude model poses ostentatiously in front of a mirror, Newton stood slightly behind and to the left of her in a long mac and white tennis shoes, with his lens trained on her curvaceous figure and the fall of the light across her body. To the right of the frame and out of the way of the reflection, however, sits another figure; her face is framed with glasses and her hair is cut in her signature dark bob, her chin resting on her hand as she leans heavily forwards. Alice Springs watches over the proceedings neither possessively, nor in awe of her husband in his working environment. She seems to be daydreaming – perhaps about her own work, perhaps about a later engagement, silently providing equilibrium in the 'King of Kink's' frame.

This seems to have been the case throughout Newton and Springs’ long marriage. As legend would have it, a 27-year-old Helmut Newton first met Alice Springs, née June Browne, who was four years his junior, when the actress stepped into a photography studio hoping to pick up some extra work as a model, and resisting his advances, found herself instead conceding to work as a sales assistant to him. Newton, for his part, had already seen his fair share of controversy: born in Berlin to a wealthy industrialist family, he fled at the age of 18, and worked for a spell as a high-class gigolo in Singapore before moving to Australia to resume his photography career. Springs, on the other hand, was a rising actress on the stage in Australia, when the pair met and fell in love. Newton recognised his equal when he met her. “It was a totally different affair from any I'd had with any other girl,” he wrote in his autobiography. "All the other girls were really only about fucking. With her there was another dimension."

The pair fell in love and moved together to Paris, where Newton quickly became a celebrity. Springs was obliged to forgo her acting career for the sake of the language, but found solace in painting, and then photography – a medium Newton also introduced her to when, one day in 1970, he found himself bedridden with flu and unable to make a job. He gave Springs a quick lesson, she stepped in to shoot it for him, and the client was none the wiser. She chose for herself the professional name Alice Springs, by blindly putting a pin in a map of the Australian outback, and began to develop a photographic career all of her own.

In spite of unity of their relationship, Springs’ work differs greatly from that of her husband. Where Newton’s photographs were famously erotic – whether capturing his own naked body standing in front of a bedroom mirror in stockings and stilettos, or that of one of the era’s great beauties, his name was synonymous with sex, high fashion, and a certain giggling playfulness – Springs chooses instead to play on her subjects’ vulnerability. She seems, in short, to emphasise the very humanity that Newton’s towering, magnificent creatures have no need of. It’s this divergence in their styles which comes into its own in Us and Them, a book they first published together in 1999, which places their photographs of themselves and of one another side-by-side with images of various models and celebrities. It’s a powerful and moving tome, not least for the two different yet equally captivating approaches taken within it; it documents the difficulties which accompany a life lived in the spotlight, as Newton’s was, and the determination required to create a partnership which can endure in spite of it.

Newton was very aware, and even proud, of the difference between their styles. "This book shows the work of two photographers: one who has dedicated his whole life to photography, the other who has been an actress and a painter before she has taken up the camera seriously if somewhat sporadically," he wrote in the introduction. "What to me is the interesting aspect of this book is the fact that neither one has in any way influenced the other’s way of approaching their subjects. I can see the truth and simplicity in the portraits of Alice Springs. As for myself, I recognise the manipulation and editorialising in my photographs." Springs echoed his sentiment. "A woman photographer can never, ever get what a man can out of a woman," she once told a reporter. "I used all the acting skills I had to make people relax, dwell within themselves and just look at me."

Joy, intimacy, pride and vulnerability all have their part to play, of course, but ultimately, Us and Them is a quietly moving and prolific record of a love which shaped not one but two of the 20th century’s most important photographic talents. To one another, Newton and Springs transcended the usual delineations of husband and wife to become mentor, editor, advisor and even substitute. It seems an apt, if heart-wrenching, final bow to their relationship that, when Newton died tragically in a car accident on Friday January 23rd in 2004, Springs stepped in to replace him on the job he had been booked for, the following Monday.

Helmut Newton and Alice Springs: Us and Them is out now, republished by Taschen.