The American artist's synaesthetic compositions and kinetic sculptures form the subject of an enlightening new exhibition at Raven Row Gallery

Who? When an LA Times review of her work referred to contemporary artist Channa Horwitz as a housewife, it epitomised everything art historian Linda Nochlin wrestled with in her pioneering essay in 1971, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Despite studying with James Turrell and Allan Kaprow at CalArts in the 1970s, and exchanging letters with Sol LeWitt, Horwitz remained very much an outlier of the California art world until the last few years of her life.

The Los Angeles native created hand-drawn algorithms combining basic principles and strict geometry to generate measured patterns, many of which resemble Aztec prints from a distance. Like her successful male colleagues, she was interested in bringing together colour, movement, sound and light, and introduced unbendable logic into the realm of west coast minimalism with her synaesthetic compositions.

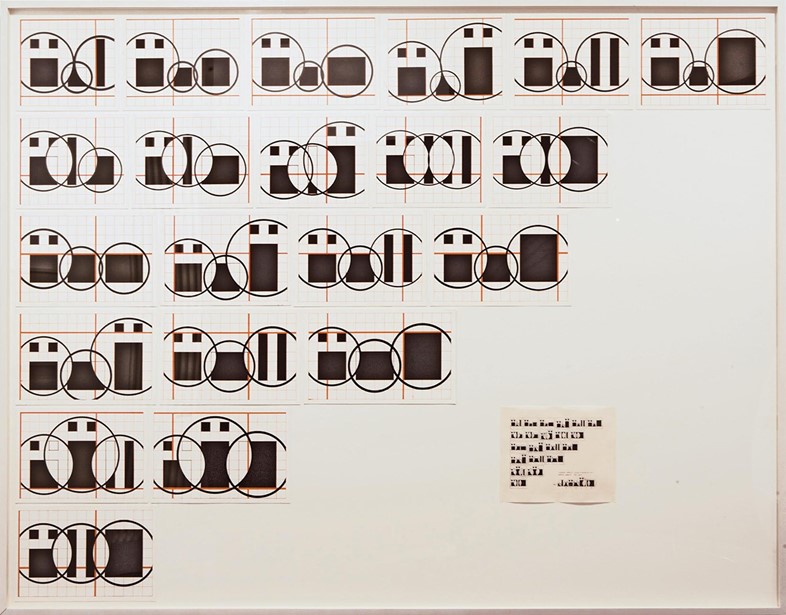

Her breakthrough moment in fact grew out of a rejected proposal for an ambitious kinetic sculpture, as part of LACMA’s innovative Art and Technology exhibition in 1968, which infamously featured no female artists. Diagrams she drew detailing the sculpture’s movement went on to inform her work for the next four decades.

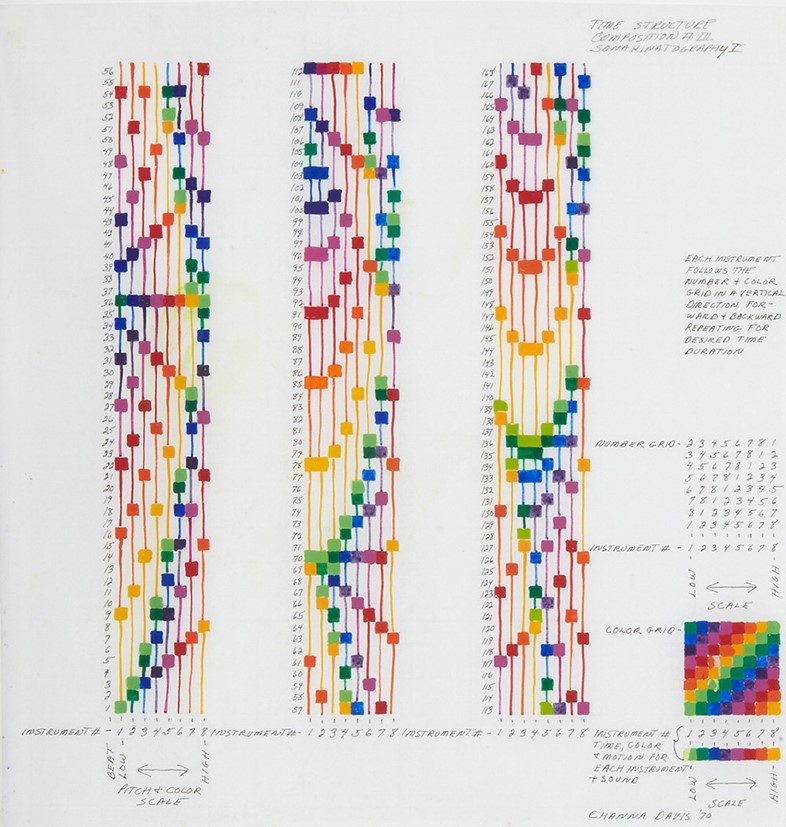

What? Horwitz’s Sonakinatography, a colour-coordinated system of notations based solely on the numbers one through eight, was, in particular, an unlikely meeting between new age thought and mathematical reason. The series took shape as a collection of labour-intensive drawings, and as each number corresponds not only to a colour, but also to a duration or beat, these intricately checked and ruled works on paper can function as visual scores or instructions for music or dance.

Drawing was Horwitz’s preferred way of working, mostly on Mylar graph paper with ink and milk-based paint, and she spent the majority of her 50-year career expanding on Sonakinatography – a term of her own invention combining the Greek words for sound, movement and notation – and another group of works, Language Series, first started several years earlier.

With time she increasingly encouraged younger artists to perform interpretations of her work, and one of her last projects saw Horwitz create an arrangement in collaboration with Y8 Art and Yoga Studios in Hamburg, translating principles from her Language Series into an immersive installation relating directly to the bodies of yogis.

Why? In 1964, casting a glance back over her time studying art at California State University, Horwitz moved on from the programme’s expressionist agenda and instead coined her rigorous, controlled visual language. By confining herself to a few simple rules, she rebelled through discipline and discovered the patterns and shapes that would become a lifelong fixture in her work.

“I have created a visual philosophy by working with deductive logic,” she wrote in Art Flash in 1976. “I had a need to control and compose time as I had controlled and composed two-dimensional drawings and paintings.”

Channa Horwitz is on display at Raven Row Gallery until May 1, 2016.