As we wait for the 2015 winner to be announced, AnOther uncovers the pearls of wisdom behind Britain's most controversial art prize

Ever since its foundation in 1984, the Turner Prize, named after prolific painter JMW Turner, has been uniquely placed in the British art industry; it straddles respect and derision with a charismatic nonchalance, one foot in the aristocracy and the other in the dirt – making it slightly idiosyncratic in its approach and all the more fascinating for it. Every year it is awarded to a British artist under 50 years old for an outstanding exhibition of their work in the previous year, and now in its 31st edition, it has a rich and varied history.

As the winner of the 2015 Prize is announced in Glasgow, AnOther recalls five history-making moments from three decades of the Turner’s archive – from a slip of the tongue from superstar Madonna, and Grayson Perry's sartorial splendour, to an Emin-hosted pillow fight and some due defiance courtesy of the Stuckists.

1. Don’t let The Man get you down

One of those rare art industry beasts which offends the establishment even as it flatters it, the Turner Prize has reached its vaunted position in the art world partially by virtue of its tendency towards controversy. Onlookers in the upper echelons of British society have made no secret of their disapproval in the past: in 2007 the UK culture minister Kim Howells dismissed the prize, and all of its nominees, as “conceptual bullshit”, to which remark Prince Charles responded with gusto. "It's good to hear your refreshing common sense about the dreaded Turner Prize,” he wrote. “It has contaminated the art establishment for so long."

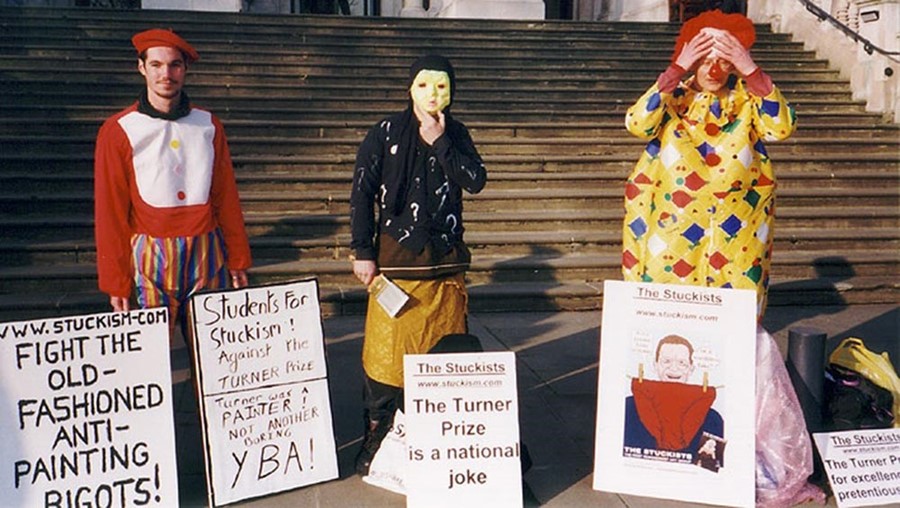

In 2000, the prize even attracted the attention of the Stuckists – an international art movement founded by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson to advocate the superiority of figurative painting over conceptual art – who dressed as clowns to demonstrate against it. Admirable if only in their tenacity, the group has demonstrated every year since, bar 2007, which it boycotted because of "the lameness of this year's show, which does not merit the accolade of the traditional demo".

Nonetheless, the prize continues to draw crowds and to mark out the most exciting in emerging talent year after year, with practitioners including Mark Leckey, Wolfgang Tillmans, Gillian Wearing and Gilbert & George among its ranks. The proof is in the pudding – the more that the establishment derides you, the more you will succeed.

2. The time is always right for a pillow fight

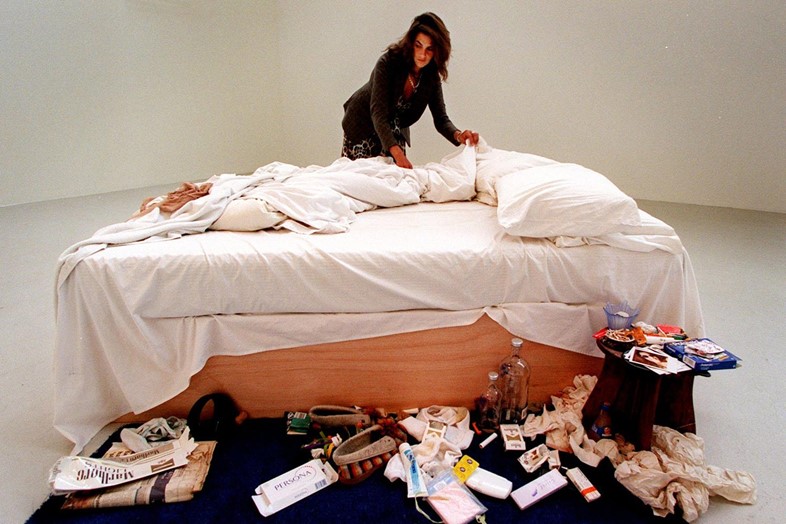

British national treasure Tracey Emin has had her fair share of Turner Prize column inches – in 1997 she left halfway through a live discussion about the prize on British TV, saying “I want to phone my mum. She’s going to be embarrassed by this conversation. I don’t care” – but arguably the best so far accompanied the showing of her seminal installation My Bed as one of the shortlisted nominations in 1997. The artwork caused a media storm at the time – visitors to the exhibition multiplied practically overnight – and such was the furore surrounding it that two visitors to the exhibition, Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi, whipped off their clothes, jumped into it, and started a pillow fight.

Now on display in the Tate Britain, the installation is rigorously patrolled by security (due perhaps in part to Yuan Chai and Jian Jun Xi’s spontaneous embrace of it almost 20 years ago), but it continues to attract a vast number of visitors. “Back in the 90s, it was all about cool Britannia and the shock factor,” Emin said in an interview on the occasion of its installation in its new home. “Now I hope, 15 years later, people will finally see it as a portrait of a younger woman and how time affects all of us. I am still very proud of it.”

3. Choose your host carefully

In addition to the endless criticism afforded judges for showing preference to works with “the shock factor,” the Turner Prize has been reprimanded over the years for its choice of host – a selection we would argue has been faultless. In 2001, for example, Martin Creed was presented the prize by the sensational provocateur Madonna, who prompted outrage by swearing on live television before the 9'o'clock watershed. "At a time when political correctness is valued over honesty I would also like to say "Right on, motherfuckers!" she proclaimed in conclusion to her speech. The attempt to bleep out the offending word failed miserably, and Channel Four was subsequently issued an official telling-off by the Independent Television Commission.

4. Wear your best frock to collect your prize

In 2003, Grayson Perry was awarded the prize for his understated and intricately textured pots, which, though on first glance appear merely decorative, in fact communicate complex ideas around sex and mortality. His acceptance of the much-lauded prize is one of the best-remembered in its relatively short history – due largely to the fact that he attended the presentation dressed as his female alter-ego Claire, wearing a pink sateen baby doll dress, red patent Mary Janes, and with a matching turquoise bow in his neatly-bobbed auburn hair. “It’s about time a transvestite potter won the Turner,” he announced in his acceptance speech, his low voice reverberating proudly. His memorable acceptance is proof, if any was needed, that a strong outfit lasts the test of time.

5. If everybody likes what you do, you’re probably doing it wrong

The list of previous Turner Prize-winners whose entries have been derided, disparaged and ridiculed, both by the industry and the general public alike, is extensive and broad-ranging. From Damien Hirst’s winning 1995 piece, Mother and Child, Divided (a mother cow and her calf divided into two halves and preserved in formaldehyde) to Martin Creed’s Work No. 227: the lights going on and off (which comprised an empty room whose lighting flicked on and off at intervals, and which so infuriated fellow artist Jacqueline Crofton that she threw eggs at its walls) the prize has a history of maddening its visitors. The takeaway from this consistently recurring phenomenon? There's nothing good to be had from being a people-pleaser: those with something worth hearing to say ought say it loud and proud, with no regard for the consequences.