Rebus at Simon Lee exhibits readymades from a trans-generational cabal of artists in order to communicate the timelessness and singular power of what arguably remains the most radical concept in the canon of art history.

Rebus at Simon Lee exhibits readymades from a trans-generational cabal of artists in order to communicate the timelessness and singular power of what arguably remains the most radical concept in the canon of art history. Bringing together works by the likes of Sherrie Levine, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Mircea Cantor and John Armleder, it’s a trip into the furthest reaches of concept-driven anti-hierarchical art that reasserts the singular importance of a movement that exploded into life with Duchamp over 100 years ago. While each object feels loaded with a multiplicity of meanings – from Feldmann’s funereal collection of plastic flowers and Cantor’s tightly-packed cage of garlic bulbs, to Levine’s baby shoe comment upon consumerism (one pair of seventy-five shoes the artist bought in a thrift store and then sold in an exhibition at the legendary 3 Mercer street) – the joy of this show for the viewer comes from the unavoidable and intense focus upon subjective analysis; the need for total engagement. There is still no existent medium where the artist is less present and the viewer is more challenged, and this show is a timely reminder that certain moments in art become an eternal language, and cannot be consigned to museums, or indeed the annals of history. AnOther stepped into the conceptual gap with curator and author Mario Codognato to find out why something as simple as a heater plugged into a wall or a pair of shoes on a plinth is as relevant now as it has ever been.

What inspired you to put together a trans-generational exhibition of readymades?

It’s interesting to me that a lot of artists are still using readymades, and that, in a sense, it has become the shared language of the 20th century and this one. Because Duchamp happened so long ago, we’ve almost forgotten about what he did, but it was possibly the biggest innovation in art history – it’s really with Duchamp and the Russian Constructivists that it all changed, and it has become a universal language. In this show, I went through the work of some of the artists Simon Lee represents – very diverse in theory and practice – and I found the common denominator was that they have all used readymades at one time or another. Then I invited three artists who don’t normally work with the gallery – who also very often use readymades – to bring in a different generation; a different culture of geographic provenance.

Do you think the readymade object is unique in its ability to shift the parameters of perception and change the subjective relationship between the viewer and the object?

Definitely. This is the typical exhibition people might mock – “Hang fake flowers on the wall, rig up the radiators and buy some garlic at the market!” And, of course, that is exactly what the exhibition actually is. But because we give these objects a new life we find so many more meanings – I think it still raises a lot of questions about what the language of art is. Because the readymade became such a powerful language it has been taken for granted that you can make a work of art just by taking an object and putting it in an art context. But it’s still a powerful tool to provoke reaction or raise some questions or make a statement. The exhibition is titled Rebus – a Latin word that expresses a concept very close to the show – when you express something not by words but through objects. That is what the show tries to do, and it’s what keeps the show together.

The readymade completely strips identity out of the equation, doesn’t it?

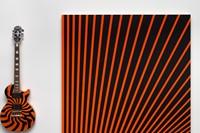

Exactly. It would be difficult to guess who these pieces are by, even if you were aware of the body of work of each individual artist, perhaps with the exception of Armleder, which is the least readymade object as it also has the addition of a painting. The exhibition is very dry and the works are very matter-of-fact and deadpan, which is interesting because the artists are all from different generations, different places – yet somehow there is quite a strong coherence.

What do you hope that someone who engages with this exhibition will experience?

There’s a resistance in all of these works – in that passage of still being an object and still being ‘nothing’ – that provokes some sort of short circuit, and I think in that passage and that gap it will give something to the viewer. I hope it is one of those exhibitions. Whether you’re totally familiar with these kinds of things, or you’re totally unfamiliar, it will certainly not leave you indifferent like another kind of exhibition could. I think it’s still really provocative. If you look at Underestimated Consequences by Mircea Cantor – an artist from Romania – it raises questions about national identity and immigration, and many other social issues connected to being foreign somewhere. In particular, this work refers to that because it’s made of garlic, and garlic has a lot of meanings in that part of the world that it does not necessarily have in the west. But I think it’s also ironic that he wants to make a modernist sculpture out of garlic, which obviously has a life of it’s own and will sprout and be very different towards the end of the exhibition. This is my interpretation, perhaps, but it may also raise a question about modernism generally, and how somehow it’s not something detached from traditional history or life.

There’s a fairly obvious parallel with Fluxus. Do you think it’s still the most radical idea in contemporary art that anything can be a work of art and everyone can be an artist?

Yes. And when they expressed that it was like a thousand years ago in terms of the advances in technology. It could be debatable that everybody could be an artist or that everybody is an artist, but these days everybody can somehow produce a video, or take photographs and enhance them – everybody has more and more and more ability, at least technologically to, in inverted commas, “create something”. At the same time as this points towards an art with non-aesthetic values or something non-hierarchical, the question can anyone be an artist, or are we all artists, is still there, because undoubtedly some people have more talent than others, and the question of talent is also quite a complicated one.

Rebus at Simon Lee Gallery runs until September 3 2011