As his new retrospective opens at Tate Britain, we explore the events and unwavering dedication to his subjects that underscores the work of lauded British photographer Don McCullin

For many, the name Don McCullin is synonymous with the searing depictions of conflict captured by the lauded British photographer – in Vietnam and Cambodia, Biafra and Bangladesh, Northern Ireland, Beirut and beyond – over the course of his 60-year career. A soldier hurling a grenade with all the strength and poise of an ancient discus thrower in Hue; a starving albino child in Biafra, his limbs so skeletal as to cause a visceral lurch in the pit of your stomach; a refugee mother from east Pakistan calmly clutching her sobbing baby to her cheek at the Indian border, her eyes directed right at you, seeing through you. These are the images that McCullin risked life and limb to document, and which, between 1966 and 1984 during his tenure as a correspondent for The Sunday Times, were delivered to the heartily stocked breakfast tables of Britain’s middle classes – a vital portal to the unimaginable brutality and bloodshed occurring overseas.

It is no wonder then that McCullin, the first living image-maker to be honoured with a solo show at the Tate Britain, is frequently referred to as a “war photographer”. This is a term that he himself shuns, however, and which the newly opened retrospective seeks to contextualise. “McCullin hates being called a war photographer – he feels that it’s the equivalent of being termed an abattoir worker, and prefers to see himself as a photographer who has devoted much of his life to documenting war,” explains Aïcha Mehrez, assistant curator of contemporary British art.

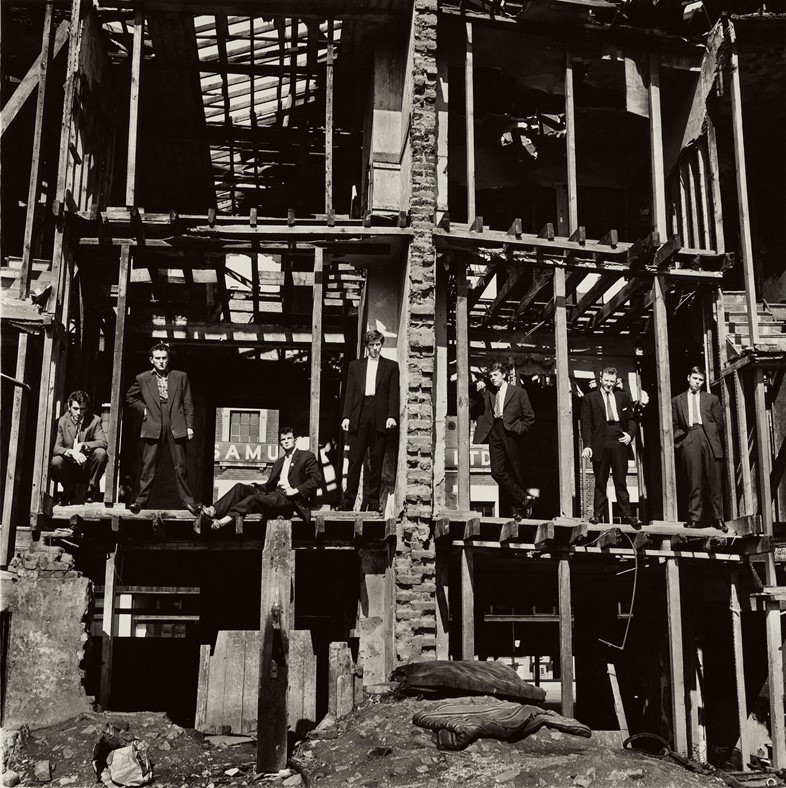

In order to demonstrate “the scope of McCullin’s career”, Mehrez tells us, the show is organised chronologically, and intersperses the 83-year-old photographer’s various assignments abroad with his ongoing forays into British documentary photography – the two genres that have most preoccupied him throughout his life. “In the first room, you see the first professional image McCullin took in 1958,” says Mehrez. She is referring to the now-iconic shot The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, depicting an infamous London gang, suited and booted amongst the remains of a dilapidated building in Finsbury Park, where McCullin himself was born and raised. McCullin, then just 23, sold this picture to The Observer, alerting the UK press to his remarkable talent and never looking back.

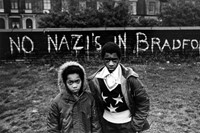

“What’s interesting is that by the time he took this picture, Don had already experienced a lot of violence and upheaval,” Mehrez tells us. “He had been evacuated three times in his childhood; he’d been the main breadwinner for his family since the age of 15, when his father died, and he’d already spent two years serving in the RAF. So by then he'd already cultivated the intense emotional awareness and enormous capacity for empathy that would go on to define his work.” Indeed, what makes McCullin’s predominantly monochrome oeuvre so extraordinary – whether he’s turning his lens to a shell-shocked marine in the throes of battle, two young boys in a Bradford park or dramatic scenes of disarray on the streets of Londonderry during ‘The Troubles’ – is not merely the artfulness of composition or the inherent sense of timing it boasts, but the sheer compassion and commonality it encapsulates.

“Of course the aestheticism of conflict is contentious, but that is something McCullin is extremely wary of. He has felt a lot of guilt about being a photographer of atrocities, also because he feels his images haven’t done enough to bring about change. So he has always employed what he describes as his ‘tools’ – which are his head, his eyes, his heart,” says Mehrez. “Once, when he was asked why he so often depicted hardship, ‘It’s because I know the feeling of the people I photograph. It’s not a case of: there but for the grace of God go I; it’s a case of: I’ve been there.’”

Yet not all of McCullin’s work centres on the cruelty and suffering he has borne witness to over the decades. In his archive there are a number of wonderful observations of what Mehrez terms “the humour, eccentricity and resilience of British people” – look no further than his magnificent shot of four staunchly serious sunbathers, perched purposefully in deckchairs on a seaside pier in Eastbourne. Similarly, he has increasingly turned to still life and landscape photography in recent years, lovingly documenting ensembles of homegrown mushrooms and plums, and bronzes collected on his global travels, as well as the undulating fields of Somerset (where he now resides), Scotland and Northumberland. Although, as Mehrez points out, these are nevertheless imbued with a sense of foreboding somehow – “some of his pictures of the Somerset plains are quite hard to differentiate from the ones he took of the Somme battlefields; you can almost hear the hum of helicopters overhead” – and his eyes are always open to social injustice (like the fact that many of these open stretches are the result of multiple dairy farms closures). A collaboration with Alexander McQueen – following the designer’s illicit printing of McCullin’s war photography on his A/W96 Dante collection – has seen McCullin’s photography permeate the world of fashion too, and he continues to photograph Sarah Burton’s collections for McQueen.

Just as McCullin has demonstrated considerable cautiousness and care over the decades he’s spent portraying the many examples of inhumanity inherent in our world, he has committed himself wholeheartedly to ensuring this exhibition is as good as it can be. “We worked with Don very closely,” says Mehrez. “We spent hours at his kitchen table going through negatives – he has some 60,000! And then he printed every single work in the show himself, so that they are all what he calls ‘the best print’.” The result is a magnificent overview of a man who has dedicated himself, with passionate integrity and unwavering skill, to his medium and subjects. And man is the operative word. As McCullin himself once said, “I operate not as a photographer but as a human being. I try to balance what I photograph not as a photographer but as a person, a man, and photography has got nothing to do with it. It is just something I have learnt, it is just a way of communicating.”

Don McCullin is at Tate Britain until May 6, 2019.