As an exhibition of both new and archive collages opens at Modern Art, London, the radical feminist artist describes her “magpie-like” practice and having to objectify herself in her work

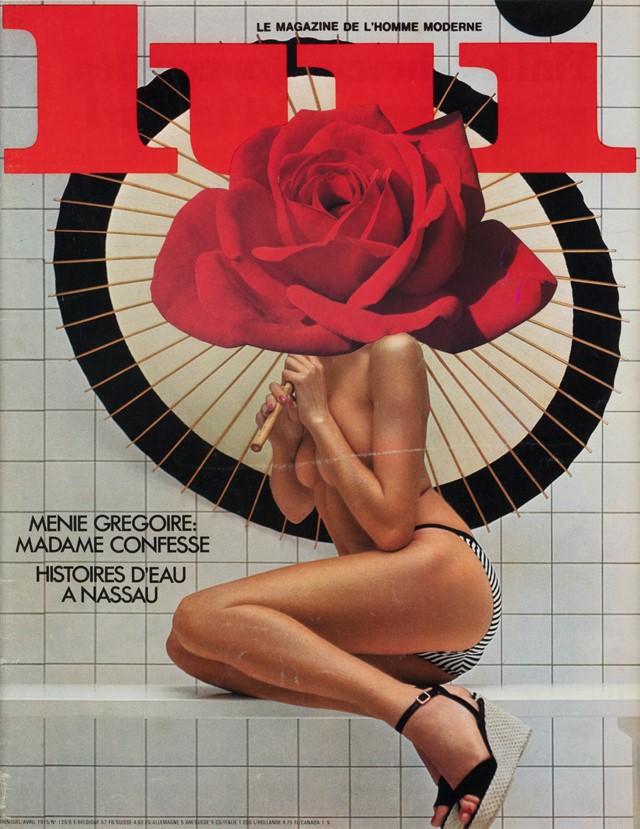

Linder is an indefatigable artist, and one whose pleasure in art-making is palpable. Her work first entered the cultural lexicon four decades ago via her cover for the Buzzcocks’ 1977 Orgasm Addict single, which was created from her student bedroom in Salford and has become so iconic that it’s spawned an entire exhibition of contemporary reinterpretations. Her subversion of pornographic images and her 70s peers have meant that then and now, Linder’s work is often prefixed with “feminist” and “punk” – and with good reason (despite having become a brand-co-opted hashtag in the case of the former, and an almost-respectable, diluted adjective with the latter).

Speaking ahead of the opening of her solo show at London’s Modern Art gallery of her collage pieces and those informed by Ithell Colquhoun’s Mantic Stain works, she’s as enthused today about her process – and the idea of making female voices heard – as ever. “I love experimentation, as I do get bored of my own cuts or marks or voice,” she says. “Heaven forbid I should get comfortable in what I do!” That restlessness has meant that her work vacillates between her famous photomontages to performance or choreographing a ballet to vast public commissions such as her Art on the Underground piece, The Bower of Bliss, to music-making – predating Gaga by a good 30 years, Linder performed at the Haçienda in a meat dress. Here, speaking in her own words, the artist discusses her practice and process, as well as sharing her thoughts on feminism.

“In the mid to late 70s we were all so poor, none of us had studios so our work was made in tiny bedrooms. We never thought in terms of the ‘art world’ or art funding or representation – no galleries would even look at the work we were making at the time – so we were just thinking about how to get those images out into the world. We had very limited means: of course it was pre-computers and there were only two photocopying machines in Manchester, neither of which would photocopy my work as they said it was pornographic. There was something very interesting when time was moving so slowly – obviously it was very frustrating because you feel invisible so much of the time, but I think invisibility grants agency. Maybe now we should cultivate more of a pause before we just automatically put an image out into the slipstream [on Instagram]. Holding back is a very attractive proposition.

“‘Feminism’ used to be seen as a dirty, ugly word by mainstream media. When I was a teenager in a small village near Wigan feminism to me was the most glorious, wonderful and slightly occluded movement. I didn’t know anybody else who read the books I read or got excited about the ideas I was being exposed to. My experience of second wave feminism was a very solitary one, but it was so interwoven in my DNA. Maybe today in being bandied about it’s almost losing its currency; perhaps that’s inevitable in some ways. We all still know we’re being shortchanged somewhere, and that means the cultural exchange isn’t quite what it’s promised to be.

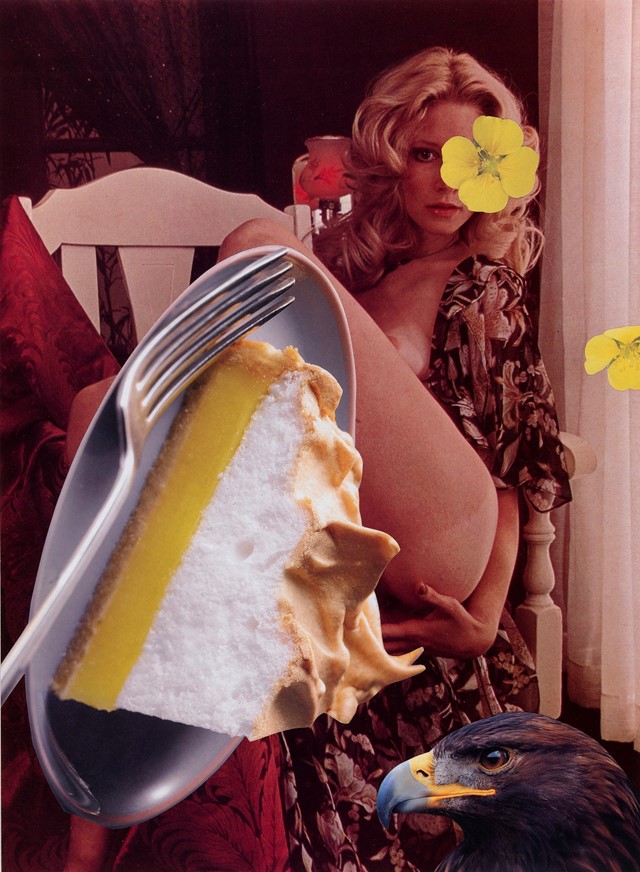

“I’m very magpie-like. I’m always looking. I think it was Picasso who said ‘I do not seek, I find,’ and there’s often that sensation when you stop searching and then go into some charity shop somewhere and suddenly find the material. I always know exactly what excites me. It’s hard to articulate what it is but it can be many things: the look on somebody’s face in a portrait or something about somebody’s dress or the colour of the sky. There’s many aspects to an image that can draw me into it. I always need space in those images so I can add, but as I add something I’m subtracting information: if I’m putting a petal over a woman’s face I’ve then subtracted her features, so it’s a bit like an equation.

“In the late 1970s I was working with found images of women and I just came to a point when it felt fair that I should objectify myself and put myself in front of the camera, using myself as a found object. I think for women particularly that psychological trope doesn’t take that much imagination because we’re often being objectified – that sensation of being looked at or portrayed in a certain way. The first time I voluntarily objectified myself felt very exciting and liberating, as suddenly you’re dominating the gaze and the lens and the composition.

“I’m rarely complacent, I always want to find different ways of making marks with lines or scalpels or a pot of enamel paint, thinking about how to make newness and new marks. I think generationally we had that delicious experience of the right to fail. I don’t think I knew when I was young what success was. The idea of The Bower of Bliss was about creating pleasurable spaces for women. It’s something we have to demand: obviously we want everywhere to be safe for everyone but let’s go above that – space should be pleasurable and safe.”

Linder: Ever Standing Apart From Everything runs at Modern Art, London, from February 1 – March 16, 2019.