In collaboration with Rome’s MAXXI museum, the astonishing work of Paolo di Paolo is entering the spotlight after Gucci’s Alessandro Michele discovered his photographs in an Italian bookstore-gallery

Who? Born in 1925, Paolo Di Paolo moved to Rome in the aftermath of World War Two to study philosophy with nothing but a small cardboard suitcase and a third-class ticket. It was here in the Roman evenings between the mid-40s and early-50s that he began to mix with the artistic crowd that would soon become his second family. The scene is easy to set: groups of young determined students sip negronis and beers while leaning on ancient alley walls. Artists like Mario Mafai flit through the streets with Gruppo Forma 1; they dine in small restaurants off Piazza del Popolo where artists pay for meals with paintings, plotting to rebuild the country from the rubble of war. It was here that Di Paolo would decide to pursue photography, a choice which saw him become one of the great reportage photographers of Italy’s post-war revival.

What? A compact camera in a shop window caught Di Paolo’s eye one day as he passed through Rome’s Termini train station: “I didn’t understand the first thing about the Leica but it was a lovely object.” The following year he was contributing his own photographs to Il Mondo, a new weekly magazine founded and directed by Mario Pannunzio. He soon became one of the publication’s leading contributors and eventually its most prolific photographer, supplying 573 images for its pages.

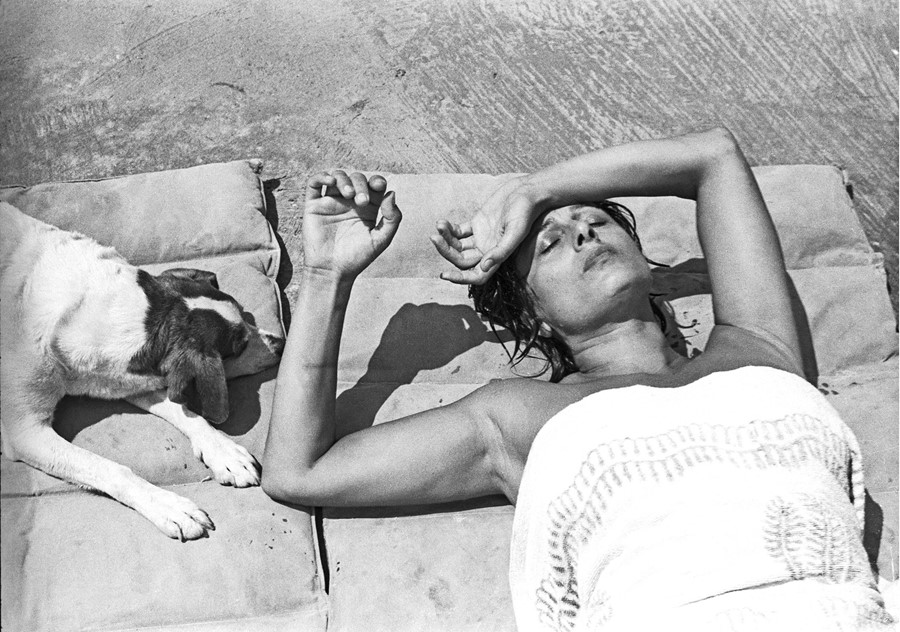

Di Paolo’s work illustrates the economic boom that erupted in Italy after the war, but also the poverty that persisted for so many. Post-war Italy was “a country of startling contrasts,” in the words of the writer and journalist Mario Calabresi. It was a place in which Di Paolo was able to capture girls walking along the Viareggio promenade in mini shorts, and others in Campobasso walking with veils covering their hair. People now travelled on everything from donkeys to planes; the rich appeared richer, and the poor poorer. Among these contradictions, the cultural capital of the new age became Di Paolo’s speciality. Rome’s golden era was just beginning and the wealth of talent that flocked to its historic centre became one of the main focuses of his work. His relaxed and “unprofessional” manner led to an astonishing range of profiles: Pier Paolo Pasolini at home with his mother; Sophia Loren laughing at the Cinecittà studios; Tennessee Williams playing with his dog on the beach. His gaze fell on everyone with equal compassion, whether women working in rice paddies in the Po valley or Italy’s exiled king.

Why? When Silvia, Di Paolo’s daughter, was looking for a pair of skis in the family’s cellar in the 1990s she uncovered a case filled with 250,000 negatives of her father’s work. Until that moment, aged 20, she hadn’t even known her father had worked as a photographer; when Il Mondo closed Di Paolo had packed away his camera. “I realised I would have to submit to the style and taste of others, instead of working to my own standards. I wanted to keep a relationship of trust with the people I photographed... I wanted to go on in my own way,” he said.

Gucci’s creative director Alessandro Michele also came across Di Paolo’s work by chance, rummaging through a bookstore-gallery in Rome. He saw “a mosaic of stories and empathy, imbued with passion, respect, authenticity”. In a collaboration with Rome’s MAXXI (the museum of the arts for the 21st century), thanks to Michele Gucci has now gathered more than 300 of Di Paolo’s images to present a compelling portrait of Italy’s evolution between 1954 and 1968.

Di Paolo branded himself an “amateur” throughout his career, reasoning “amateurs only follow their instinct, they are free agents... professionals can’t say no.” Relatively unknown abroad despite his famous subjects, this collection looks to set the record straight, and finally recognise just how influential the “amateur” can be.

The exhibition and book Paolo di Paolo. Mondo Perduto. Fotografie 1954 – 1968 will be released in March 2019.