As a new performance celebrating the life of the ambassador for the underworld opens in Edinburgh, we consider his inimitable impact

What did Leigh Bowery actually look like? It’s hard to tell. He was his own creation, “modern art on legs” to quote Boy George, a shape-shifting celebration of the obscene. In his short life, he provoked a gamut of emotions, from wonder and admiration to revulsion and disgust. “If I have to ask, ‘Is this idea too sick?’” he said, just after an AIDS benefit when he’d had an enema on stage and sprayed the front row, “I know I am on the right track.”

Today he is synonymous with London, Taboo and the canvases of Lucian Freud, but Bowery’s beginnings are less well known. His story starts in the small Australian suburb of Sunshine, as choreographer and performer Andy Howitt discovered last year when he encountered a statue by him in the National Gallery of Melbourne.

Intrigued by the journey from small-town boy to rubber-suited ringleader of London’s New Romantic club scene, Howitt has created a 40-minute dance, spoken word and musical performance piece called Sunshine Boy, currently showing at the Edinburgh Fringe. Drawing on conversations with Bowery’s family in Sunshine, and his friends from the London years, Howitt explores his subject’s life, times and psyche, from his childhood in Sunshine to his arrival in London in 1980, meteoric rise to notoriety and death from AIDS in 1994, when he was just 33.

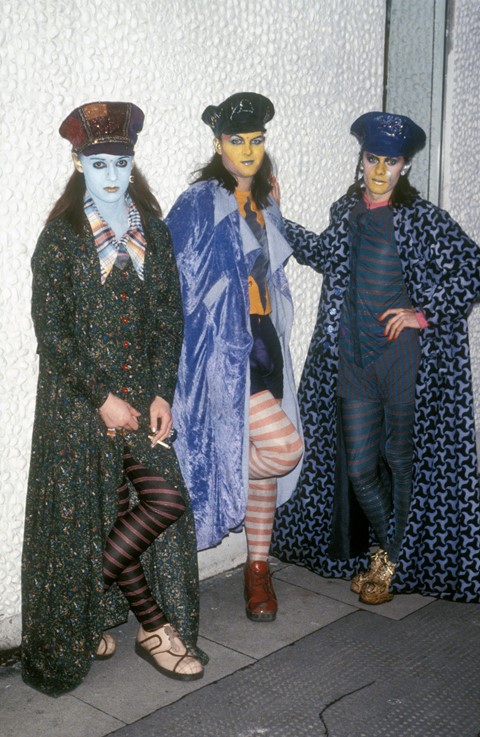

Bowery’s capacity to provoke, delight and disgust was partly rooted in his physicality. 6ft 3in and 17 stone, he capitalised on his attention-grabbing size with outlandish outfits he designed himself and debuted on the door of his epoch-defining Soho club night, Taboo. Each week it was something new: sequinned dresses, viciously tight corsets, fake vaginas, garish body paint, gimp masks, Gaffer-taped cleavages, a giant tulle pompom headdress and a turd-shaped body suit. His influence can be seen in the work of the fans who flocked there – in the clothes created by John Galliano and Alexander McQueen, and in Boy George who wrote a stage musical called Taboo in its honour. Vivienne Westwood declared him to be one of the two most influential designers in the world; the other was Yves Saint Laurent.

In perhaps his most infamous performance, as part of the show with his band Minty, he “gave birth” to his wife Nicola Bateman – who, strapped naked and upside down to Bowery’s stomach, her face wedged in his groin, was concealed under a fake belly. At a signal, she would emerge covered in fake blood, raw sausages playing the role of umbilical cord, as Bowery hollered at the ceiling, and the audience either roared with approval or marched out in disgust.

But as much as he provoked, he also inspired, and his outsider appeal only served to open doors to the inner circle of London’s cultural elite. He performed in David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes video, appeared in the windows of the Anthony d’Offay gallery, posed for Lucian Freud, designed costumes for Michael Clark, appeared in adverts for Pepe Jeans, art directed the Unfinished Sympathy video for Massive Attack and hosted a segment on The Clothes Show, taking tea in Harrods in a sequinned body suit and rubber tights. He was the poster boy for freaks, an anarchic force who was welcomed into drawing rooms and onto television shows as an ambassador from the underworld. He used this platform both to keep pushing, shocking and horrifying, and to smuggle unpalatable references into the mainstream – his famous painted dot face was a nod to Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer that caused facial lesions for AIDS sufferers.

Bowery was diagnosed with the AIDS virus six years before his death, but he kept it a secret to the end. His wife only found out when he was hospitalised in the winter of 1994, and he left instructions that after his death she was to tell everyone he had gone to Papua New Guinea. At the time, his legacy seemed to be confined to the portrait by Lucian Freud – the vast, bald man stripped of his garish costumes and transformed into no less a dramatic confection of colour and flesh.

But as Howitt’s show demonstrates, Bowery still resonates – his confrontation of negative body image, celebration of the outlandish and impolite, his rejection of societal norms and endless creativity is evident across popular culture today, from evolving beauty standards and clubland fashion to Ru Paul’s Drag Race and the ubiquity of fetish and sex clubs. In many ways, the world Leigh Bowery sought to provoke has caught up with him at last, but what is certain is that, had he lived, he would be finding new ways to shock us all.

Sunshine Boy is at Dance Base in Edinburgh at 7:15pm until August 26, 2018.