An insightful New York exhibition and accompanying catalogue reveal the auteur’s formative work in photography, taken as a curious teenager for Look magazine in New York

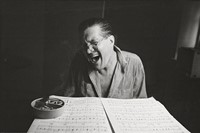

Master filmmaker Stanley Kubrick never went to college. Instead, in 1945, at the age of 17, he took a job as a staff photographer at prestigious New York publication Look magazine, and got his schooling on the city streets. His assignments were wonderfully varied – taking him from the boxing ring to the dancehall, from the subway to the sets of films and television shows – and, as such, his subjects spanned everyday folks going about their business through circus performers and movie stars.

He left the magazine five years later, having captured “around 13,000 images,” according to Donald Albrecht, Curator of Architecture and Design at the Museum of the City of New York. The museum – which owns most of Look’s archival photographs and contact sheets, from the 30s until the early 60s – is currently host to a new exhibition of Kubrick’s photographs from this period, co-curated by Albrecht and offering incredible insight into the director’s formative years behind a different kind of camera. “Later in life, Kubrick said something like, ‘By the time I was 21, I’d learnt how the world worked,’” the curator tells us – and the images on display, and printed in a covetable accompanying catalogue by Taschen, are a tangible testament to this fact.

The show is organised chronologically to show what Albrecht terms “Kubrick’s development from a man who’s photographing very disparate things to one who is very quickly putting together long-form essays that really show a cinematic eye”. His first essay for the magazine was titled Life and Love on the New York Subway and features an arresting image of a young couple sleeping soundly on one another in a train carriage. The man’s hat is pulled down over his eyes, his hand tucked tenderly into the chequered overcoat of his peacefully snoozing lover. “That picture’s been staged,” Albrecht reveals. “The woman is Kubrick’s future wife. Some of the pictures in the series are candid, some of them are set up.” The fact that, right from the start, Kubrick was constructing scenes to pack a narrative punch says much about his zeal as a storyteller who would not long be satisfied by documentary alone.

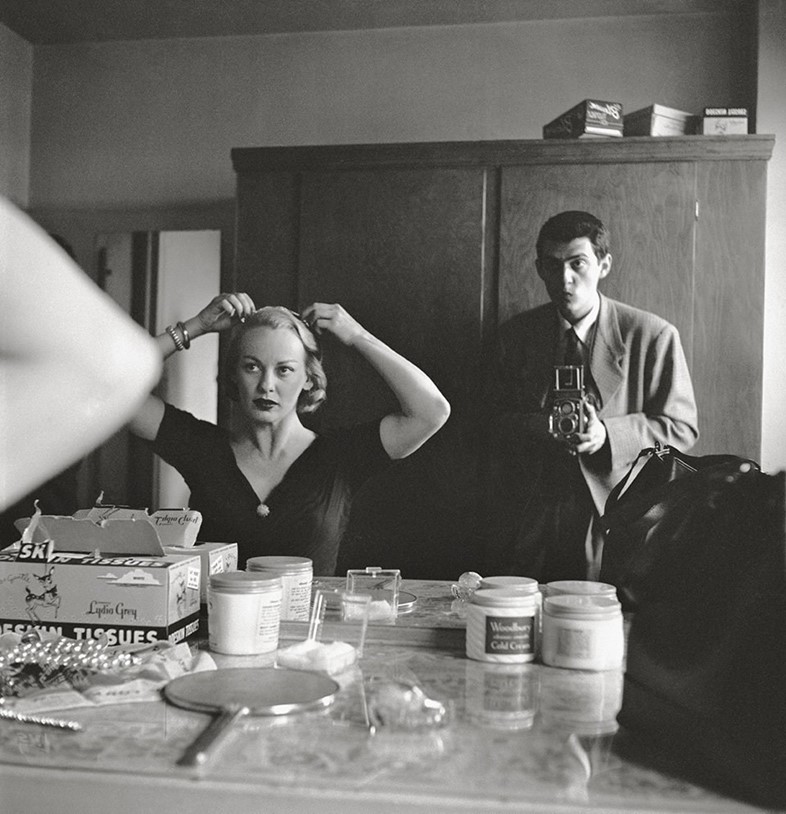

Many of Kubrick’s films boast an inherent voyeurism – look no further than A Clockwork Orange or Eyes Wide Shut for the most explicit examples – and this too was a theme already at play during his Look years. “In a lot of the photographs there are people looking at people, so he’s watching people watching people,” Albrecht observes with a chuckle. “For instance there’s a very interesting shoot he did of showgirls on stage at a New York City nightclub. Rather than just focusing in on the showgirls, he pulls back so that you also see in the foreground a group of men and women – often men – looking at and talking about the girls. So he’s framed the performance in the act of watching the performance, and that’s a characteristic you find in the films.” In another playful shot, the photographer snaps actress Faye Emerson (the so-called “first lady of television”) in her dressing room mirror, including himself – fresh faced, wide-eyed – and his camera in the picture. Not only a whimsical study in watching, the work also shows the young cameraman getting a valuable first taste of life on set.

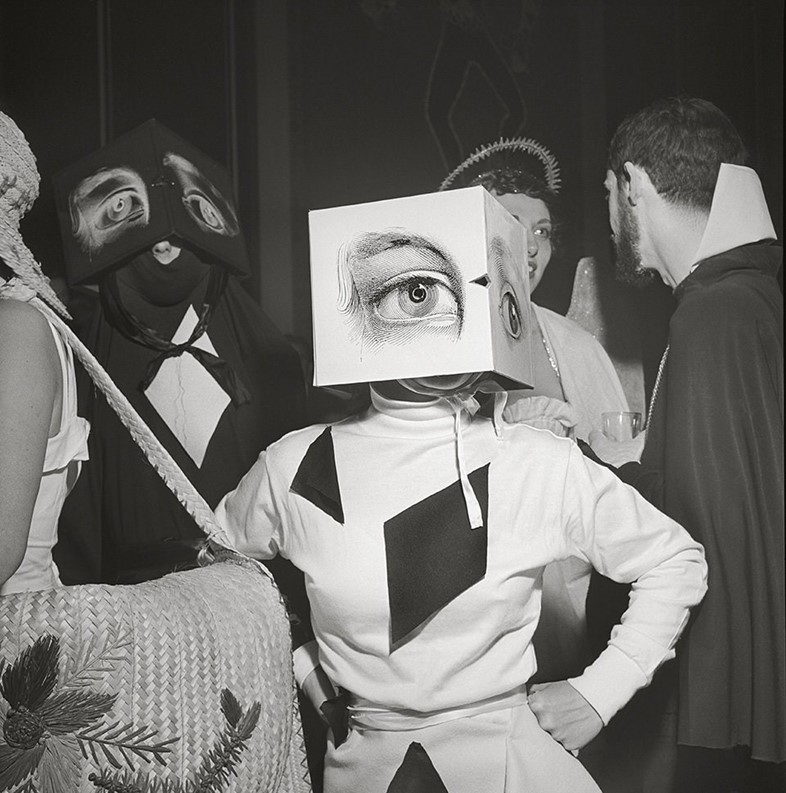

Another characteristic already obvious at this stage is Kubrick’s tendency towards the taboo, something we are privy to courtesy of the many outtakes not published by Look, which were nevertheless preserved in the archive. “The magazine was family orientated so he’d have known they wouldn’t print them,” says Albrecht. In one shot, for instance, taken in Sarasota, Florida, Kubrick captures a member of the Ringling Brothers Circus, bare chested, his body covered in tattoos and his nipples bearing a pair of huge metal rings. “That’s not a shot that the magazine’s going to publish but it clearly shows Kubrick as a young man, his eye focusing on the more illicit themes you see in the film work.” The images also demonstrate Kubrick’s obvious delight in documenting performance, from the shot of an American boxer named Rocky Graziano standing proudly nude in the shower, his gaze fixed unblinkingly on Kubrick’s lens, to a pair of party goers in Cubist masks with unsettlingly huge eyes – a picture with a distinctly Clockwork Orange strangeness to it.

The clearest link between the director’s early forays into photography and his work as a filmmaker, however, can be seen in the series of pictures he took in 1949 of a boxer named Walter Cartier. Cartier, Albrecht tells us, would go on to form the subject of Kubrick’s first ever film, a documentary named Day of the Fight, shot in 1951. And it’s obvious from the images that something about the athlete and his setting has ignited the director’s imagination. “The series is very cinematic,” Albrecht says. “Kubrick was very interested in film noir and its distinct crime-ridden, shadowy aesthetic. The photographs are very beautiful, the lighting is very dramatic, but he depicts very dark shadows – showing the darker view of the world that he would go on to project in his films.” New York’s shadowy underbelly and the characters that punctuated it would, of course, also carry over into his fictional films: “One of his first features is a film called Killer’s Kiss, which deals with a boxer in New York and a dancehall girl who’s his girlfriend – so the subject matter and the visual style is directly related to his photography at Look.” Indeed, it gives a double meaning to the auteur’s quote about discovering how the world worked by the age of 21. “At first it sounds like he means the world of work,” expands Albrecht, “but perhaps he also means the world of human interactions and illicit behaviour – of men and women in nightclubs, of the life after dark – that would pulse through his movies.”

Stanley Kubrick Photographs. Through a Different Lens is at the Museum of the City of New York until October 28, 2018. The accompanying catalogue is out now, published by Taschen.