Ryan McGinley’s photographs capture moments of ecstasy and abandon. His most recognised are those taken on a series of summer roadtrips across America, where gatherings of young companions are released, naked, into the country’s vast pastoral landscapes. There, seemingly unaware of McGinley’s lens, they hurtle carefree through fields of hay or corn, climb trees, writhe in snow, or lay prone under chromatic skies. Their bodies appear boundless, and can barely be held on the page.

Before that, McGinley documented New York’s downtown scene as the millennium turned, a period of artistic hedonism set against a glowering backdrop of world affairs. (9/11 would happen midway through the series, entitled The Kids are Alright.) The works, in response, are visceral, and the human body messy and uncontrolled; grazed, bruised, dripping with blood, vomit, or semen. In one photograph, McGinley photographs a friend riding through the dust of the fallen World Trade Centre towers. His photographs almost seem to be “what ifs” – what if we let go of all that restrains us?

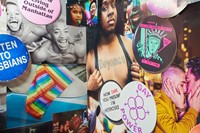

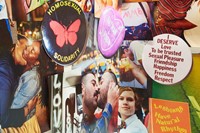

His latest exhibition, which opens in the subterranean Soft Opening gallery in London’s Piccadilly Circus station, mines similar territory. Entitled The Spirit of Pride, it is a frantic collage of queer life – photographs of LGBTQ men and women kissing are layered upon images of protest badges, many of which are from early queer liberation movements. (McGinley was helped in sourcing these by Leighton Brown and Matthew Riemer, the couple behind the Instagram account @lgbt_history.) “Queer symbols that communicate ideas, concepts, and identity within our community and to mainstream culture,” he says of this ephemera. “If you are wearing a gay badge you cease to be invisible.”

Photographs of couples kissing, which make up a number of the collaged images in the exhibition – and sit alongside those taken at Pride weekends in New York – are a recent fascination. “Kissing is a beautiful symbol of compatibility for any sexuality,” McGinley says. “But there are not enough iconic photos of queer couples kissing, so it’s important for me to help create them.” The fruits of this obligation make up much of the Spirit of Pride, and gain power for their display in such a well-travelled place as Piccadilly Circus station.

“There are not enough iconic photos of queer couples kissing, so it’s important for me to help create them” – Ryan McGinley

McGinley is a long-time activist – he has been involved with HIV/AIDS charities amfAR and ACRIA for many years – and has recently become part with New York-based direct action group, Voices 4. Begun by Adam Eli, who McGinley now considers a close friend, it is a response to the stories emerging from the Chechen Republic, part of Russia Federation, that members of the LGBTQ community were being rounded up, abducted, tortured and killed. (Eli will lead a rally on Friday evening in London, above Piccadilly Circus station, to coincide with the exhibition.) Earlier this year Voices 4 staged a “kiss-in” at the Russian Embassy in New York, McGinley documenting the embraces in the rain, unrestrained and impolite. (Some of those photographs appear in Spirit of Pride.)

The protest – one of intentional visibility and public disturbance – spoke of a dialogue between queer action groups new and old. In the midst of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, “kiss-ins” were used as one of many tactics Act Up invoked to draw attention to the lack of response from president Ronald Reagan and his administration. Later, they would hold “die-ins”, where the protestors’ limp bodies – acting out their own deaths, and the death of their loved ones – were carried away by police officers. They hoped then that they would feel the physical weight of human life.

Act Up was particularly prescient for McGinley growing up. When he was a teenager his brother was diagnosed with AIDS, and he would join him on marches in New York. “I was a teenager during the time my brother was sick,” he says. “He was living between my parents house in New Jersey and his apartment in New York City, depending on his health. I was wearing T-shirts that said ‘Safe Sex’ and badges with the pink triangle [the symbol of Act Up].”

“We were desperate to save my brother Michael’s life and get him feeling better,” McGinley says of his brother. “He needed greater access to experimental AIDS drugs. I remember going into New York with him to Act Up protests. On the ride in we’d talk about how many T-cells he had that week, and he’d be applying make-up to disguise his Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t get the drugs he needed fast enough and he died at 34. I feel like I approach my whole life through the lens of my brother’s death,” he says. “It was the birth of my queerness.”

The previous two Pride weekends in the United States – a tradition that stems originally from the Stonewall Riots in New York City in 1969 – have found attendees increasingly politicised. These are, after all, the first held since Donald Trump was inaugurated as president, with the parade now a response to the waning rights for LGBTQ Americans under his administration. No longer can the pure hedonism of the last decade be justified – now, Pride is a time to take stock, to discuss the changing freedoms queer people are afforded both inside, and outside, the United States.

“In the USA vice president Mike Pence is possibly the most homophobic politician to ever be in the White House,” McGinley says. “He is a hardline evangelical who has not supported a single LGBT reform across nearly two decades in politics. Pence has one of the worst records on equality of any vice president in history. He supports gay conversion therapy. Of course we’re all mortified.”

But McGinley refuses to give up, and his activism – much like his photographs – is energised by the euphoric hope that there might, one day, be something better. “I practise unity with my queer sisters and brothers,” he says. “I sing the song U.N.I.T.Y. by Queen Latifah to myself a lot. I like to substitute in my own words sometimes… ‘Love a ‘queer’ from infinity to infinity (you gotta let them know) U.N.I.T.Y… U.N.I.T.Y… that’s a unity’.”

Spirit of Pride runs at Soft Opening gallery, London until July 8, 2018.