A new exhibition of the Belgian artist’s seldom seen photographs and films shines new light on his playful subversion of reality

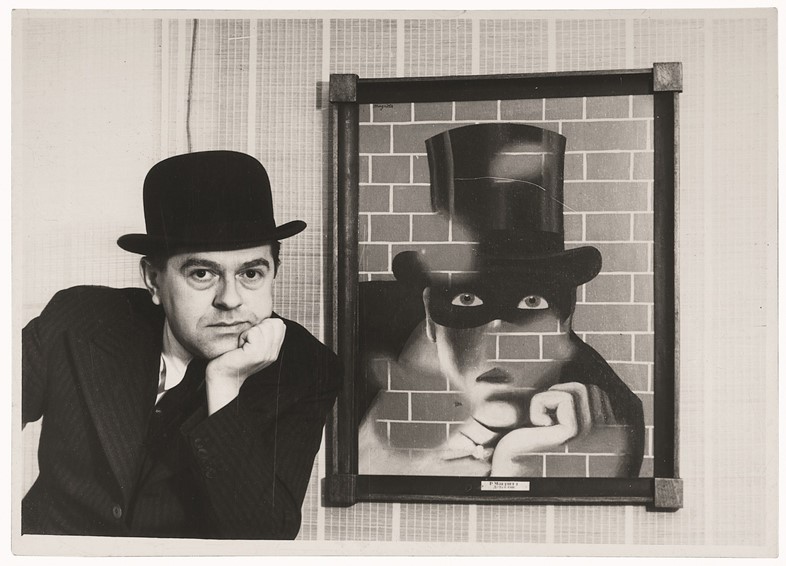

The paintings of René Magritte are famously easy to spot, owing largely to the Belgian Surrealist’s fascination with repetition – of ideas, of symbols, of entire artworks. A man in a bowler hat, for example, is definitively “Magritte” – it’s usually a self-portrait of the artist, whose father was a hatter. The same applies to umbrellas falling from the sky or objects paired with words in a manner that makes you reflect upon the very nature of objects and words themselves, as in his iconic 1926 painting The Treachery of Images depicting a pipe – another favourite symbol – accompanied by the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“this is not a pipe”).

Of course you can recognise a Magritte by its stylistic traits too – the artist’s handiwork is bold and illustrative, likely a result of his supplementary work in advertising; it’s playful and mysterious: you’re never left wondering what is pictured, but you are often left wondering why. “Magritte never wanted to show how brilliant he was as a painter,” explains Xavier Canonne, art historian and curator of new exhibition, René Magritte: The Revealing Image, at Hong Kong’s ArtisTree gallery. “He preferred to remain on the threshold of art. He was more focused on the way he expressed his ideas, on how to touch the spectator.”

Interestingly, most of these characteristics are identifiable in another lesser-known facet of Magritte’s work: his myriad photographs and films, discovered in the mid-70s almost a decade after his death. It is on around 132 such works that the ArtisTree exhibit focuses, divided into six sections that explore the various ways in which Magritte utilised photography, from the intimate snapshots he captured for family albums to the experimental works he produced as aids for his painting practice. The artist, who began working in paint in 1915, going on to study the medium at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels the following year, didn’t begin his early forays in photography until the late 1920s. “He probably bought his first camera when he moved to Paris from Belgium with his wife, Georgette, in 1927,” Canonne tells us. “He had been inspired by the famous American photo-booth, the ‘Photomaton’, that had arrived recently in Europe, and by his friend Paul Nougé, who was the head of the Brussels Surrealist group.” Unlike Nougé, however, who frequently presented his images in public, Magritte refused to exhibit or reproduce his photographic works during his lifetime, hence the fact that so few associate him with image-making to this day. “It was for him a kind of experience,” Canonne expands, “a secret experimentation.”

Be that as it may, Magritte’s images certainly stand alone as artworks in their own right, the most compelling pieces the ones where he applies the trademark concepts and imagery from his painted oeuvre to his pictures. Just as his paintings take iconography from the real world and render it surreal, for instance, the artist was determined to, in Canonne’s words, “deny photography the capacity to reproduce ‘reality’ because he preferred to imagine things, or explore what he called ‘the mystery of the universe’”. One of Magritte’s favourite methods in generating such intrigue was to obscure one object behind another, especially faces – think: his iconic painting, The Son of Man (1964), depicting a bowler-hatted figure, his features covered by a large apple. “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see,” he once explained of this preoccupation.

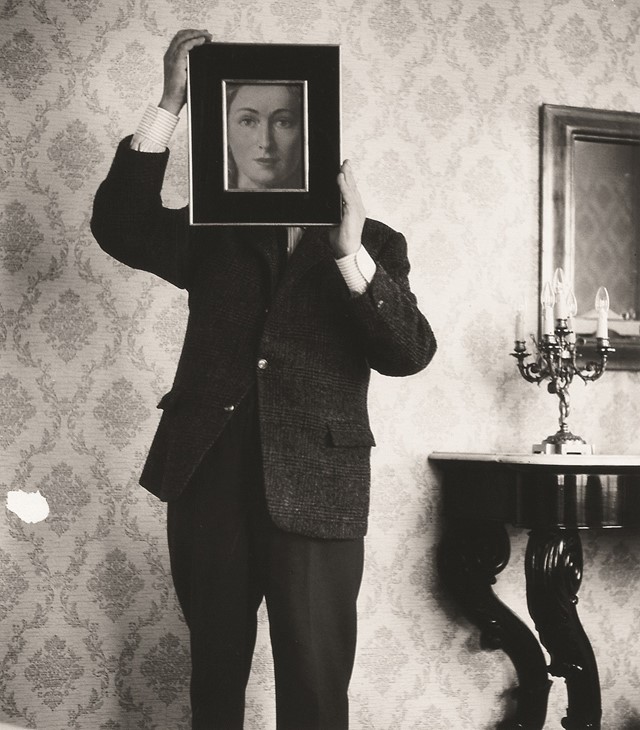

In The Giant (1937), a wonderful “anti-portrait” (to use Canonne’s words) taken of his friend Nougé on a beach in Belgium, Magritte captures the artist concealing his face behind a checkered chessboard. “This forces the viewer to concentrate on the details of his clothing and the pipe he holds in his hand,” the curator expands. In another wonderful image, a 1962 portrait of a suited Magritte taken by the photographer Shunk Kender to accompany an article on the artist in a French magazine, Magritte trades his own face with a panel from his 1954 painting The Eternally Obvious depicting a female face. “This creates a strange ‘hermaphrodite’ figure in a three-piece suit,” says Canonne. In his 2017 book, which shares the same title as the exhibition and serves as the premise for the show, Canonne expands further on Magritte’s tendency to disguise faces. “According to Magritte, a face cannot express someone’s real nature but offers only an appearance, a ‘false mirror’,” he writes. “Nor does it provide a means of knowing the person whom one is portraying or who is portrayed. It is restricted to the surface and is incapable of penetrating the mystery.”

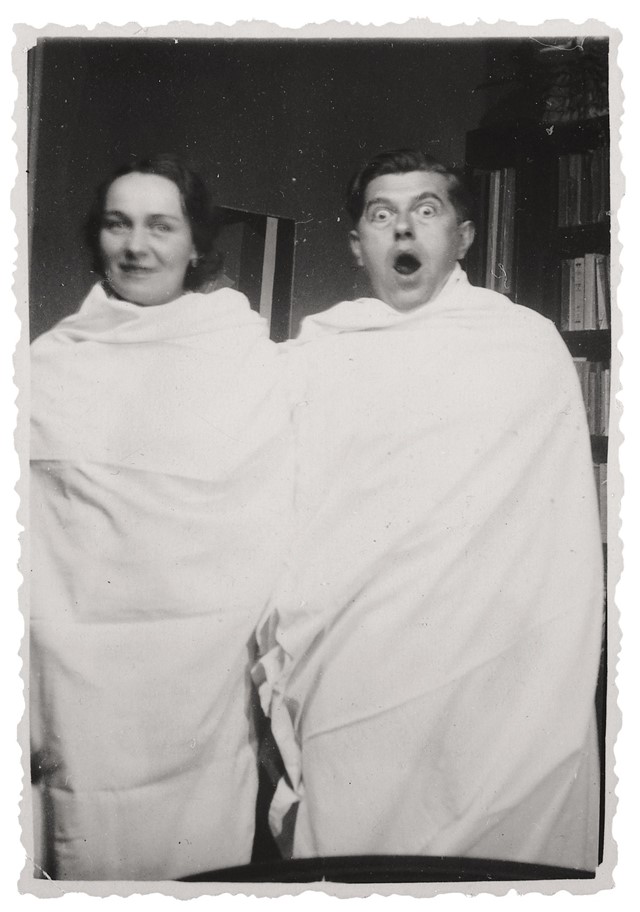

In other pictures, more examples of Magritte’s “hidden-visible” ideas are at play: in a heartwarming shot of him and his beloved wife Georgette, Georgette’s face hides most of his own as he sits behind her, while in The Bouquet (1937), the pair whimsically wrap their bodies in sheets, their heads (Georgette smiling gently, Magritte feigning an air of surprise) floating in midair. “He didn’t want to be serious in front of the camera,” Canonne observes. “He loves to play and act, as you can also see in the few movies he made in the 50s.” Such works show a lesser-known, more intimite side of Magritte – the fun-loving family man, whom the curator says he hopes visitors to the show will be surprised to encounter. “But what’s ultimately interesting to understand is that whatever technique Magritte used – be it oil, gouache, collage, sculptures, or photographs – he was, at heart, the same man, the same mind that never stopped trying to ‘enlarge the possibilities of the universe’.”

René Magritte: The Revealing Image is at ArtisTree until February 19, 2018.