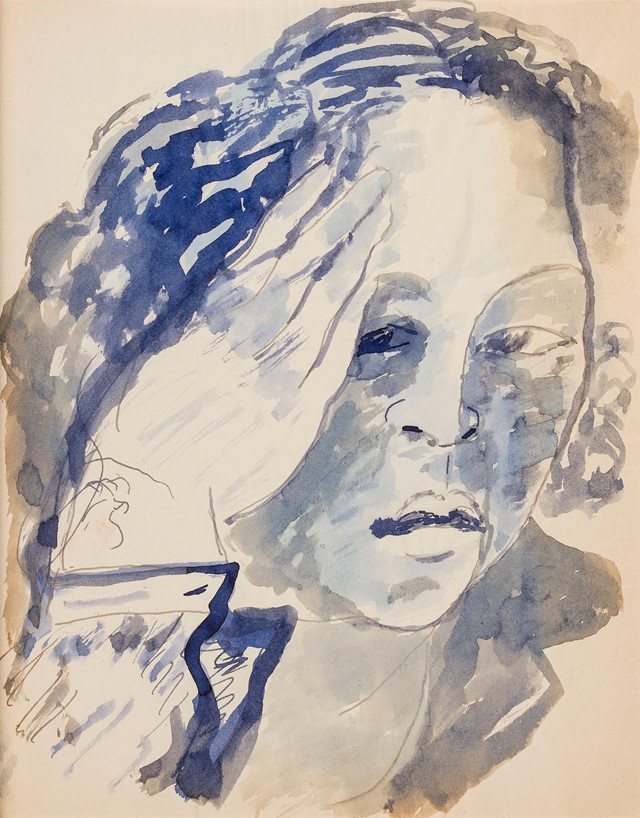

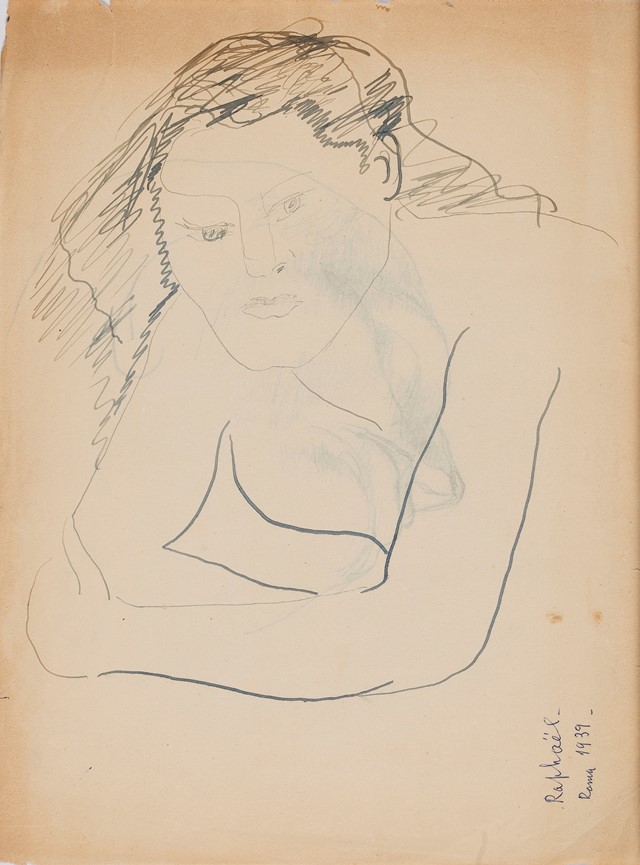

“Drawing is never lost time”, sculptor Antonietta Raphaël once noted, “it’s a clarification.” Fortunately for us onlookers the artist was always keen to clarify, and as a result, her broad archive of sculpture and paintings also includes a large collection of beautiful sketches. These works on paper focus predominantly on the female form, with stark lines giving way to rich curves; happily, Raphaël’s work remains unafraid of the nakedness it depicts, embracing the fragility and fortitude to be found in the shelter of skin. There is a sense that she sought to refine the beauty before her, like Matisse when he declared he wished to “condense the meaning” of the body by “seeking its essential lines”. By paring back, the details of Raphaël’s drawings speak all the more. In her lifetime, the artist was forced to flee her adopted home of Rome to escape the oppressive regime of Mussolini. Now, however, her work has at last returned to the ancient city in the form of an exhibition of previously unpublished works at the Museo Carlo Bilotti Aranciera di Villa Borghese.

Raphaël is best known for her role in founding the Scuola Romana in 1928, together with her husband, the painter Mario Mafai. It was here, opposite the Forum, dressed in large flowing kaftans, that the artist nicknamed “Chagall’s little foster sister” gathered creatives for drinks and heated discussion on her large terracotta terrace. The house and studio at 325 Via Cavour was soon transformed into a central meeting point for artists working against the growing fascism of the times; Raphaël was born in Lithuania, and found herself a target of Mussolini’s drive to abolish “degenerate” Jewish art in Italy, creating inevitable difficulties for her creative career. After her name appeared on a list of “artists to ban”, one friend remembers how she even kept her paintings wrapped up in towels in a closet.

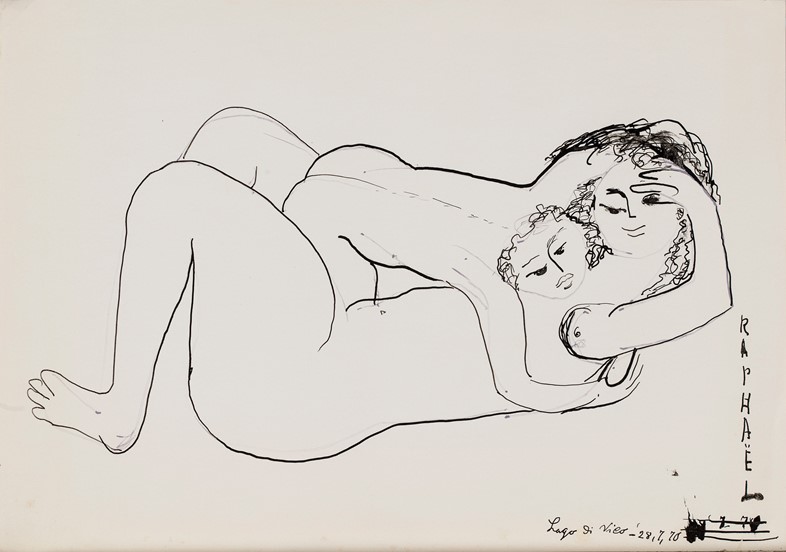

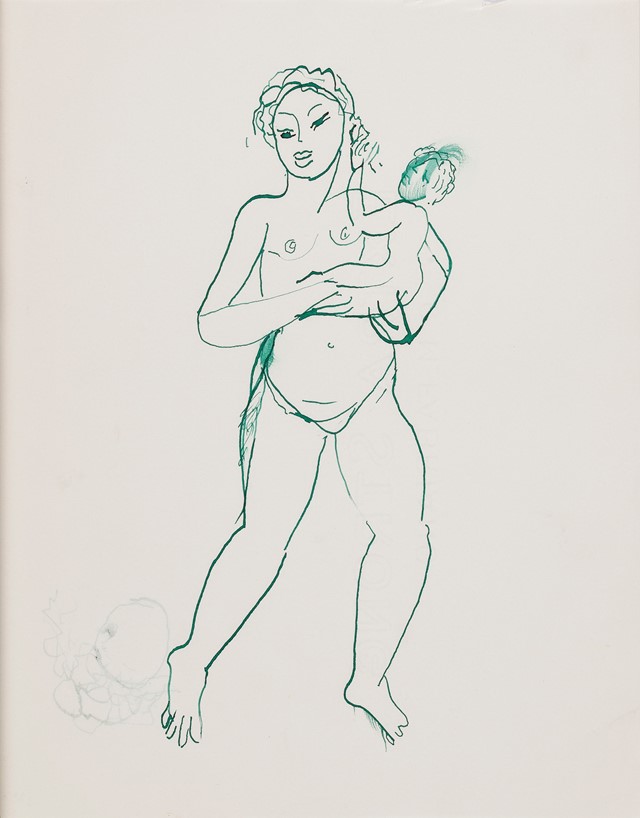

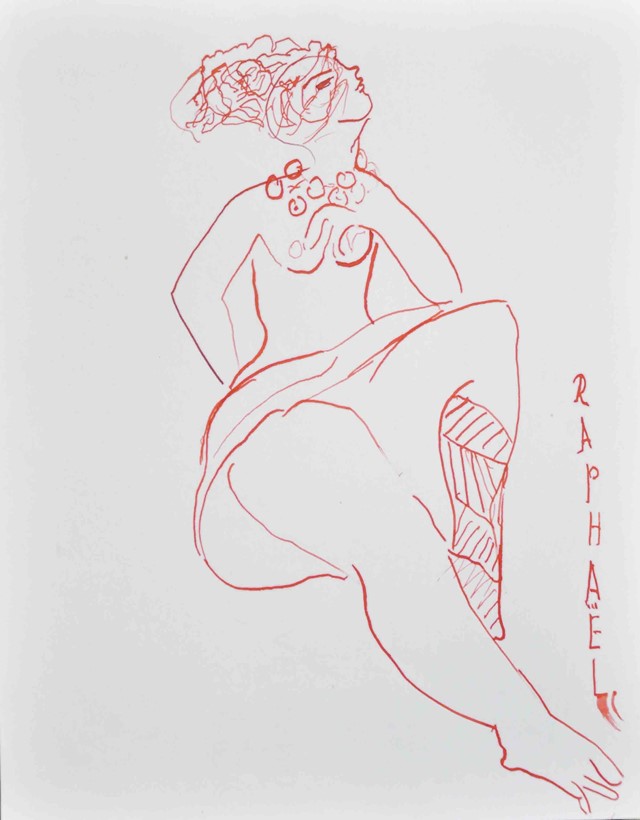

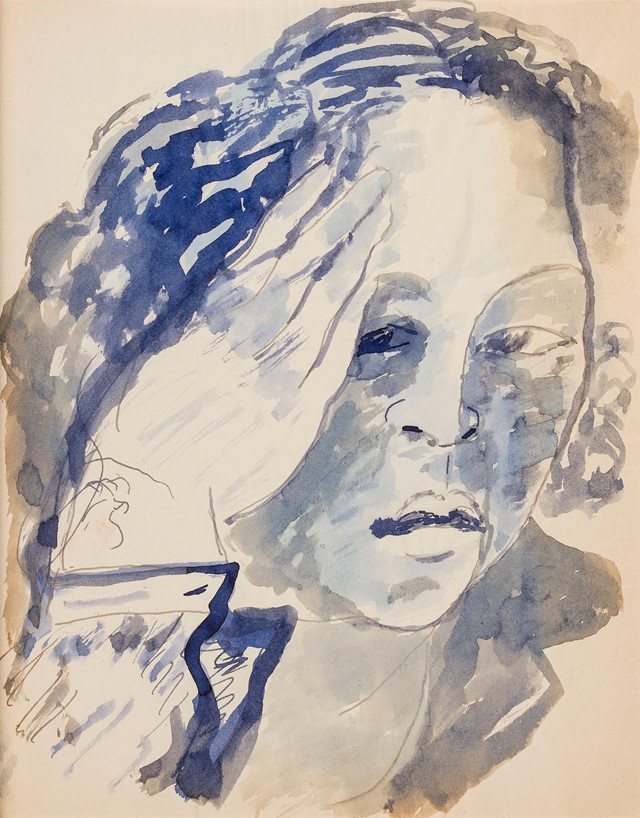

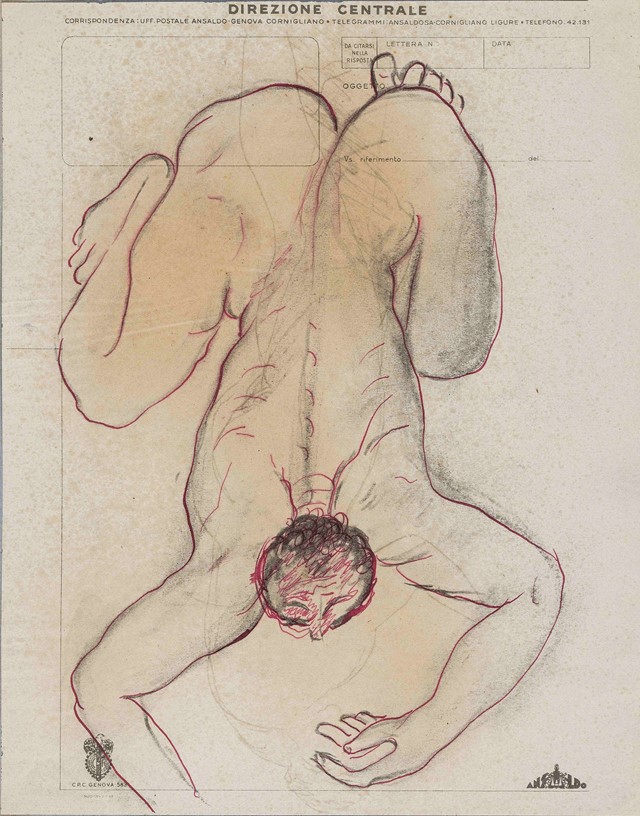

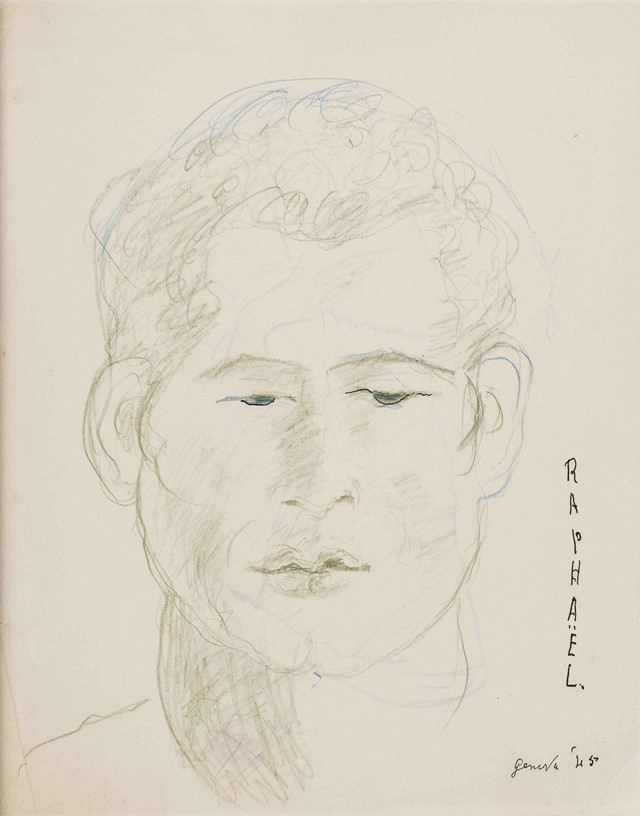

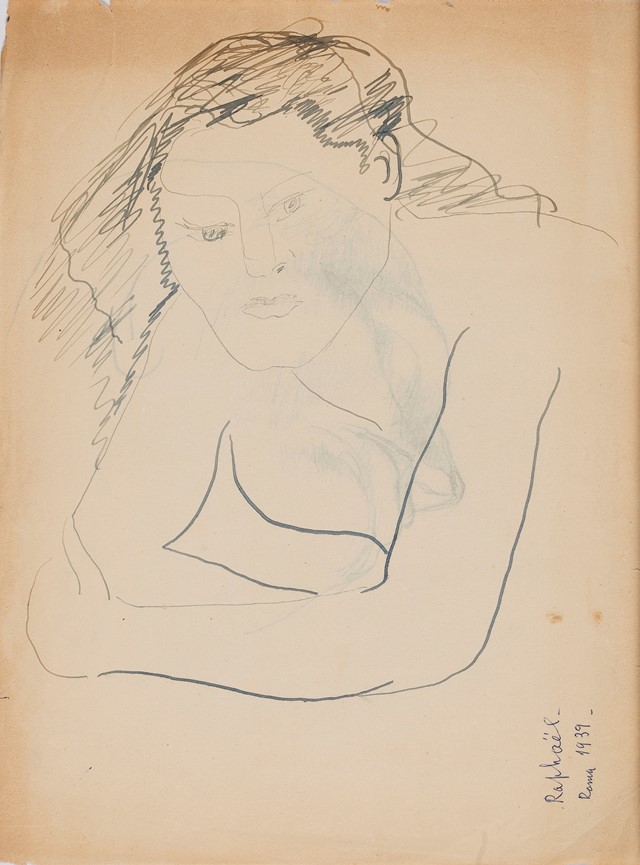

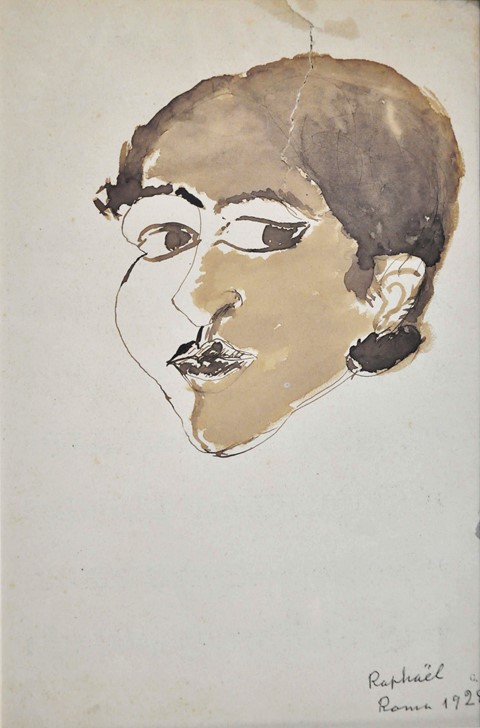

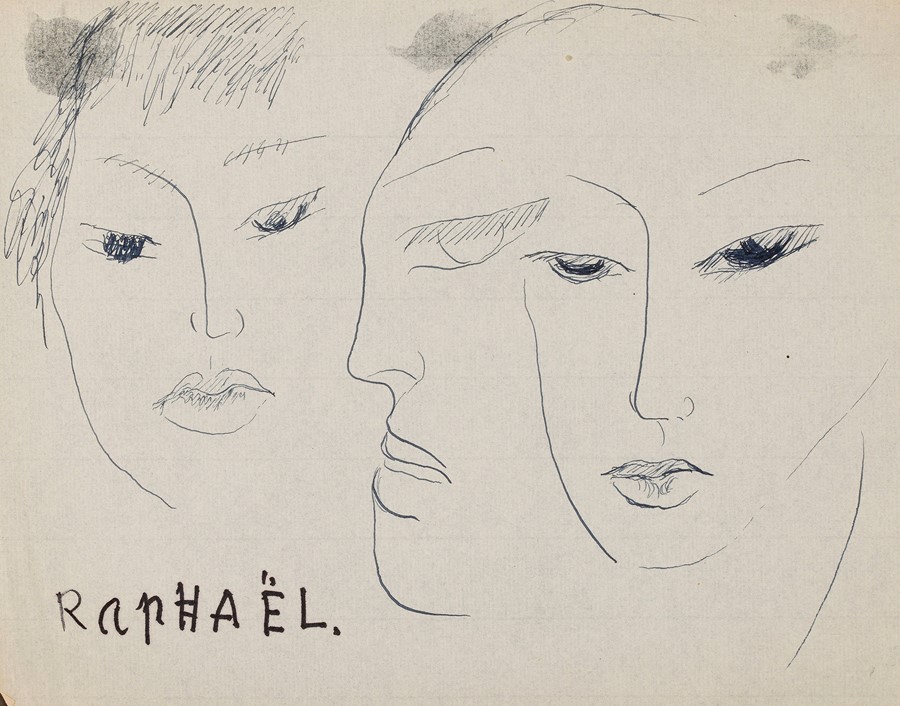

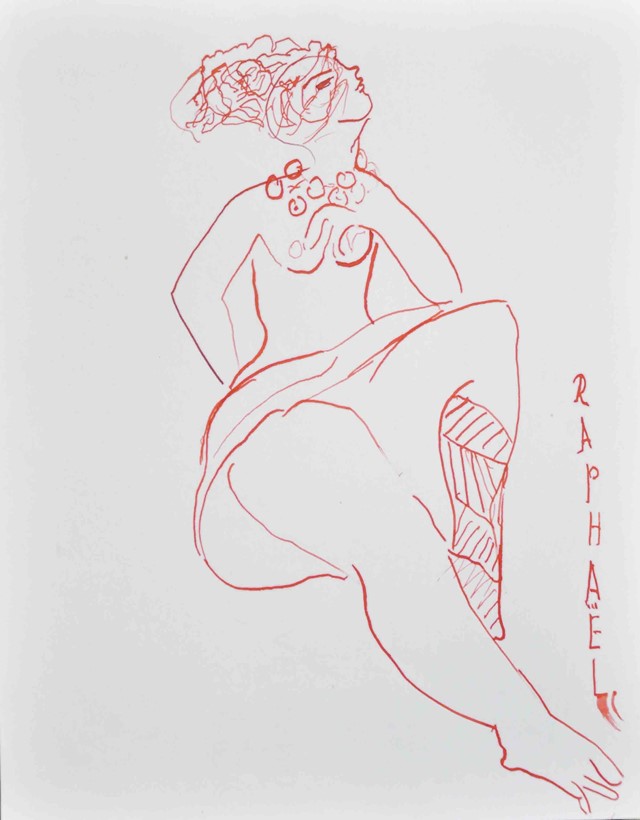

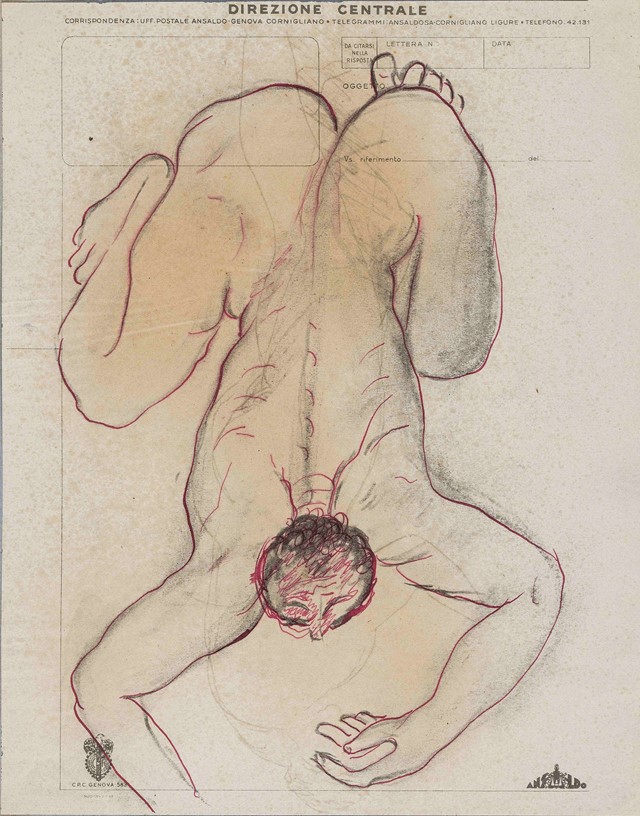

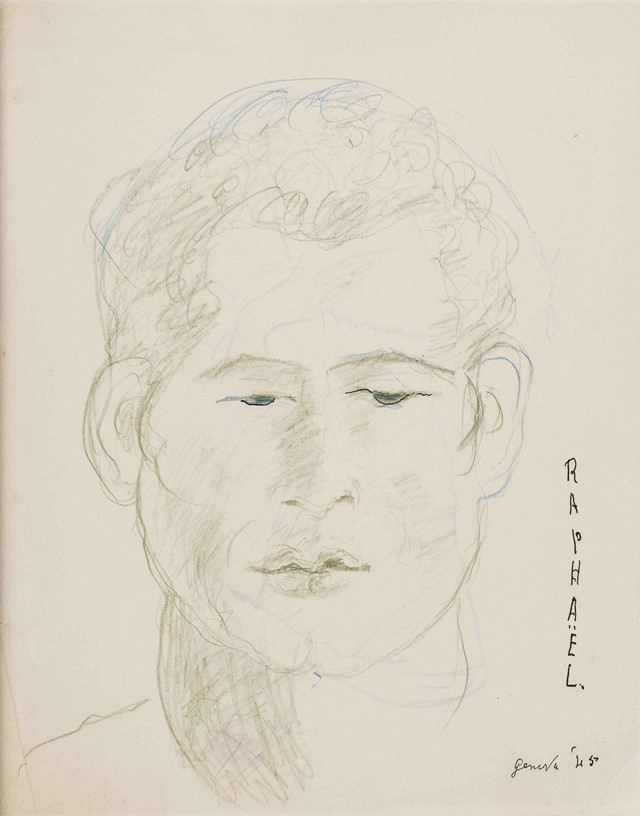

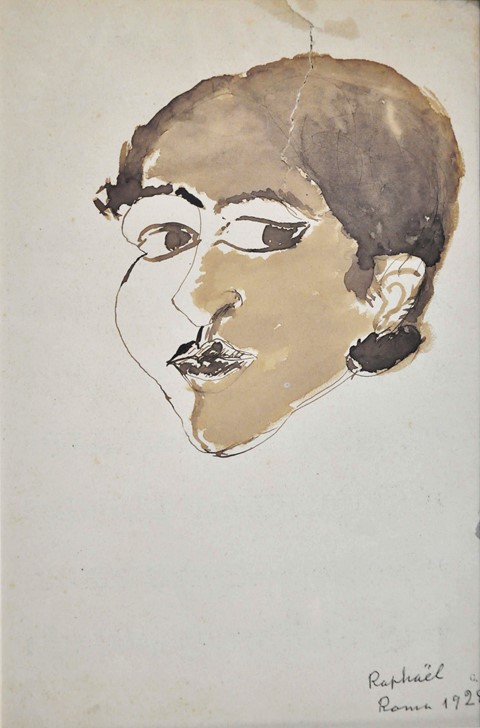

As well as stand-alone drawings, the exhibition includes studies for her sculptural works, which are set alongside the finished pieces – a curatorial decision which powerfully enhances how integral these images were to her wider artistic practice. They may be smaller than her more celebrated works, but the delicate leaves of paper still captivate: a woman’s curls radiate in shocks of red coloured ink; a triptych of faces stare out in stark monochrome. If anything, the sparseness of the medium lends itself all the more keenly to Raphaël’s dramatic shapes and formal preoccupations. In ink, against the blankness of a page there is nowhere to hide, and so eyes are drawn to all manner of composite parts: the arched curve of a woman’s hip, the soft indent of a cupid’s bow, or the ripeness of a fleshy cheek.

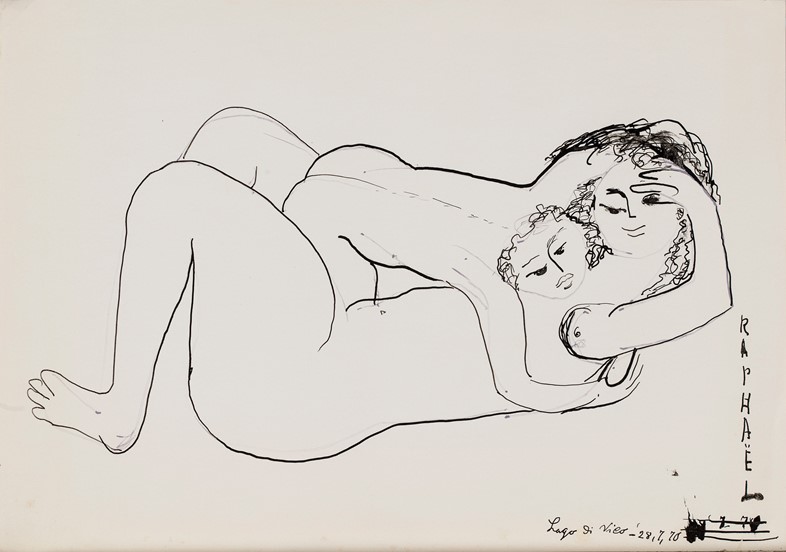

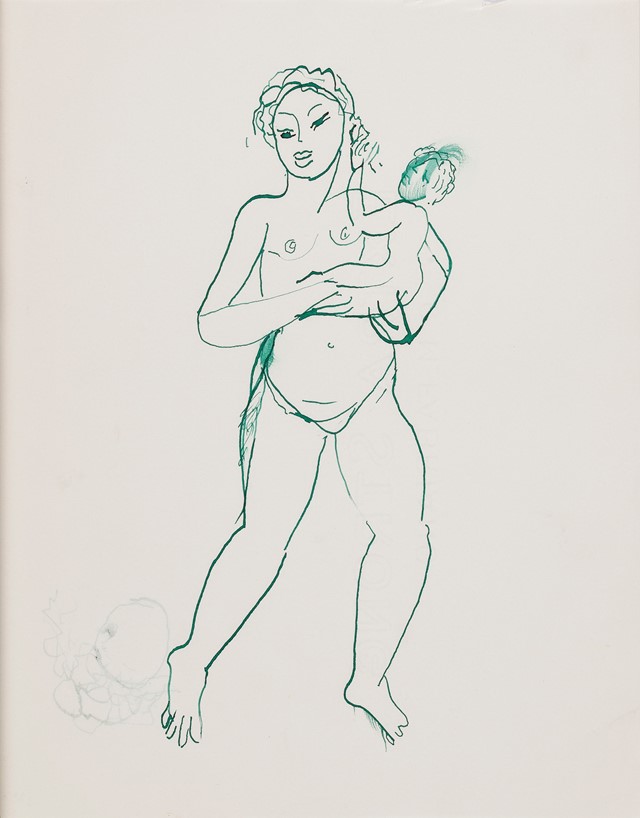

Raphaël embraced and cherished the changeability of women’s bodies. In her drawings the bending forms of lovers, the swollen bellies, and the breasts of women with newborns are made clear, their beauty secured in their simplicity. Maternity and creativity remained inextricably linked throughout Raphaël’s life. After the birth of her own daughters she continued to create, with Mafai as her most ardent supporter; “I wouldn’t want you to turn into a good little housewife,” he teased. Later she would look back and openly declare “all my life I sculpted motherhood”. When she died, the last unfinished painting that remained propped on her easel was of a woman giving birth. Mother and creator, the urgency of her identity can be felt in these marks she has left behind; in her own words: “I know that something has to merge, be born, born.”

Antonietta Raphaël Mafai – Carte runs at Museo Carlo Bilotti Aranciera di Villa Borghese until January 21, 2018.