As a new exhibition opens at Tate Modern about the enfant terrible of Modernism, we examine three of his supremely talented female muses

As the paradigmatic tortured artist, Amedeo Modigliani’s biography is now legendary. An alcoholic, drug addict and rampant womaniser, his early death by tuberculosis at 35 ended a turbulent life that feels strangely at odds with the elegance and serenity of his sculptural portraits and nudes. The enfant terrible of the Paris Modernists went largely unrecognised during his lifetime, and he staged only one exhibition, but his work now achieves eye-watering prices at auction.

All of this mythologising makes it difficult to unpick some important truths: among them, the central role his lovers played in shaping his work. Even with the catalogue of cruelties inflicted upon them, they continued to propel him forward creatively. On the eve of a new retrospective at Tate Modern which also aims to redress this imbalance, we look back at three talented women who lived under Modigliani’s towering shadow.

Anna Akhmatova

Starting an affair on your honeymoon might seem outrageous, but among the free-thinking bohemians of Montparnasse it barely raised an eyebrow. Tall and dark-haired, with an elegant aquiline nose, Anna Akhmatova sent ripples through intellectual society upon her arrival in Paris in 1910; and nobody was more smitten than the 24-year old Modigliani.

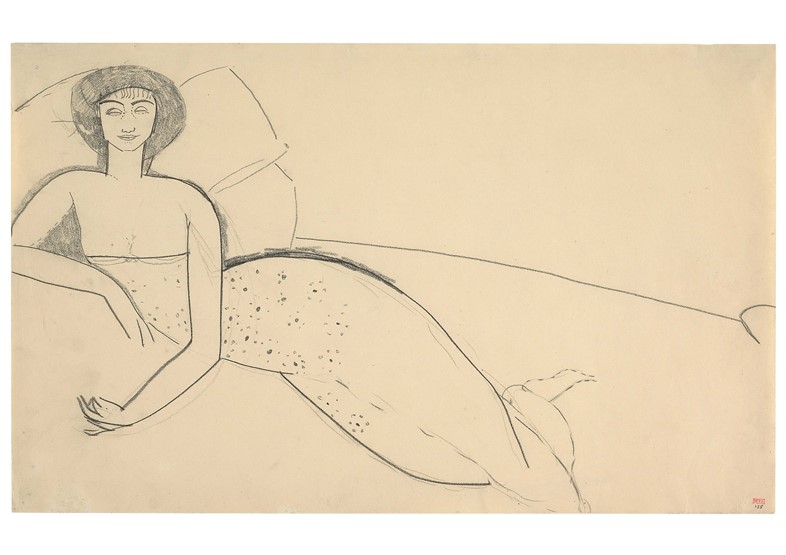

While her retail tycoon husband lunched with friends, Akhmatova and Modigliani would take walks in the park, during which he encouraged her to pursue a budding interest in poetry. But before he knew it, Akhmatova was whisked back to Saint Petersburg, with Modigliani left heartbroken. A constant stream of letters give us a remarkable insight into this fiery relationship – when Akhmatova returned the following year, he would spend hours drawing her in the Egyptian galleries of the Louvre. Within a few months she was forced to leave again, this time for good, sparking Modigliani’s downward spiral into drugs and depression.

Akhmatova herself didn’t fare much better. As an outspoken critic of Stalin, her first husband was later executed for his monarchist leanings, their son imprisoned, and a second husband sent to the gulag. She faced constant persecution under the Soviet regime, and her now highly regarded works of poetry only began to receive critical attention late in life, with two Nobel Prize nominations in the final years before she died.

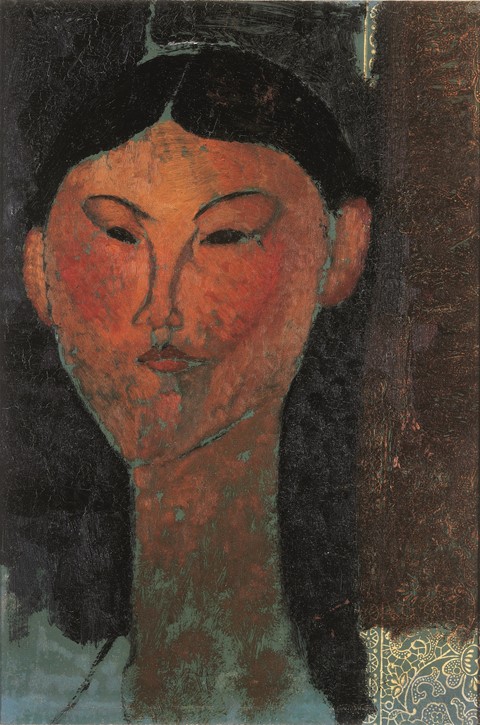

Beatrice Hastings

On encountering Modigliani at the Café La Rotonde in Montparnasse, Beatrice Hastings noted in her diary: “I sat opposite him. Hashish and brandy. Not at all impressed. Didn’t know who he was. He looked ugly, ferocious, greedy.” Not the most promising first impression – but it was a meeting that would transform both of their lives. Now 30 years old, Modigliani’s career was stalling. Prone to week-long bouts of drinking and bingeing on drugs, his inability to sell his work had driven him down a creative cul-de-sac. Hastings, five years older than Modigliani, was attracted to his bohemian charisma, and he to her independence and breathtaking intelligence.

A child prodigy, Hastings was born in Hackney but emigrated to South Africa with her family as a young girl. She was sent back to Britain to attend boarding school, due to her volatile temperament, and she flourished there, becoming a brilliant pianist, singer, equestrian and poet. Later in life she was also known as a committed socialist and a staunch advocate for women’s voting rights and access to contraception. The collision of these single-minded characters led to blistering arguments and a combustive relationship, extinguished after Hastings finally found another, more stable, lover in the series of romantic liaisons (with both sexes) she undertook while with Modigliani. Frustrated with the public underestimation of her formidable talents, she eventually committed suicide.

For many decades she was remembered largely as Modigliani’s muse, but a revelatory 2004 biography by Stephen Gray, Beatrice Hastings: A Literary Life, sheds light on her extraordinary life and letters. Long overdue a critical re-evaluation, let’s hope the new exhibition encourages new interest in Hastings’ singular intellect.

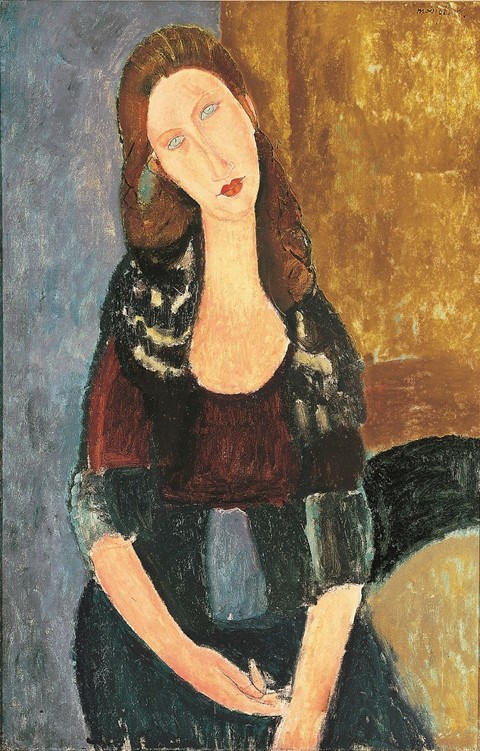

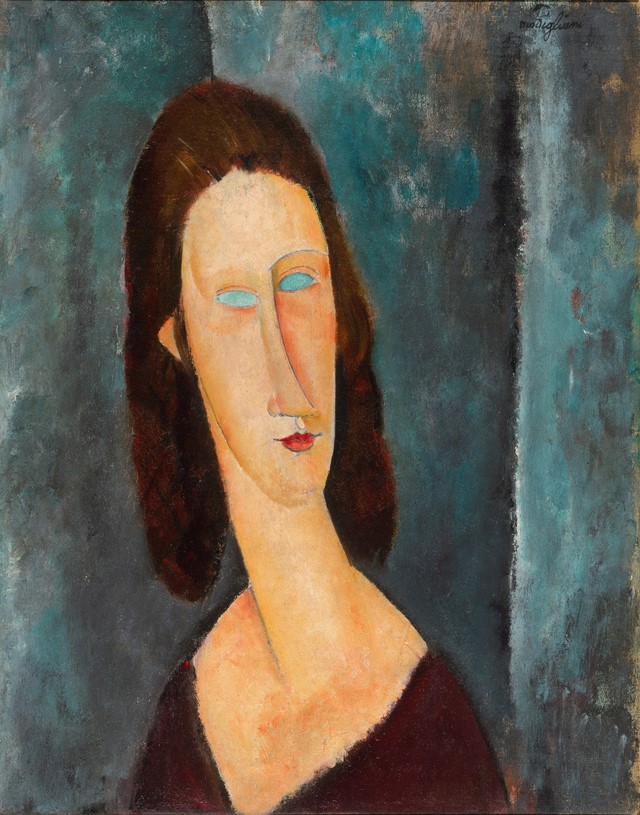

Jeanne Héburtene

By 1917, Modigliani was in the darkest depths of addiction. Even if art historians have argued that it was a result of his worsening tuberculosis – a kind of self-medicated palliative care – his behaviour was no longer unpredictable but wilfully destructive. Enter a young, shy and beautiful art student from a strict Roman Catholic family, Jeanne Héburtene, who found herself seduced by Modigliani’s scabrous charm. Moving in together, Héburtene became the central subject of Modigliani’s late career, and the closest he ever came to a conventional relationship. Together they had a daughter, also named Jeanne, and during wartime escaped to Nice and Cagnes-sur-Mer, where their second child was conceived. A talented painter of modest, meditative portraits, she continued to work quietly as Modigliani descended into mania.

During the latter stages of Héburtene’s pregnancy, her disapproving family discovered the severity of Modigliani’s illness and denied her permission to marry him. Modigliani had lost all his friends, and took to roaming the streets of Paris every night, drunk and high. One night, the now estranged (and still pregnant) Héburtene was called to his apartment, where he died in her arms of tuberculosis. A day later, Héburtene threw herself out of a window at just 20 years old, killing both herself and her unborn child. The last of the talented women driven to despair after entering Modigliani’s tangled, toxic orbit – and given her young age, surely the most tragic.

Modigliani runs from November 23, 2017 until April 2018 at Tate Modern, London.