Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas’ images have altered the course of history, and turned the whole world into witnesses, a new book attests

Who? Susan Meiselas does not care for the term photojournalist – she finds it too reductive – but she is all too often referred to as one of the greatest practitioners in the field. Since joining Magnum Photos in 1976 she has travelled to conflict zones across Nicaragua, El Salvador, Argentina and Kurdistan to report on the violence and atrocities that have taken place, as well as focusing on domestic projects that include the world of carnival strippers, the S&M club scene and evidence of domestic abuse.

Meiselas never trained formally in photography, although she taught the medium in New York public schools and studied Visual Education at Harvard. In fact, early in her career she felt no particular affinity with the static singular image or the great street photographers that had come before her (such as Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander), more often finding inspiration in film. In her new book On The Frontline she explains “despite the pleasure of making a photograph, I still feel the need to stitch it and weave it into something more. I want to know what the subject says, beyond what the picture shows. I want to explore how the viewer can be invited into the exchange.”

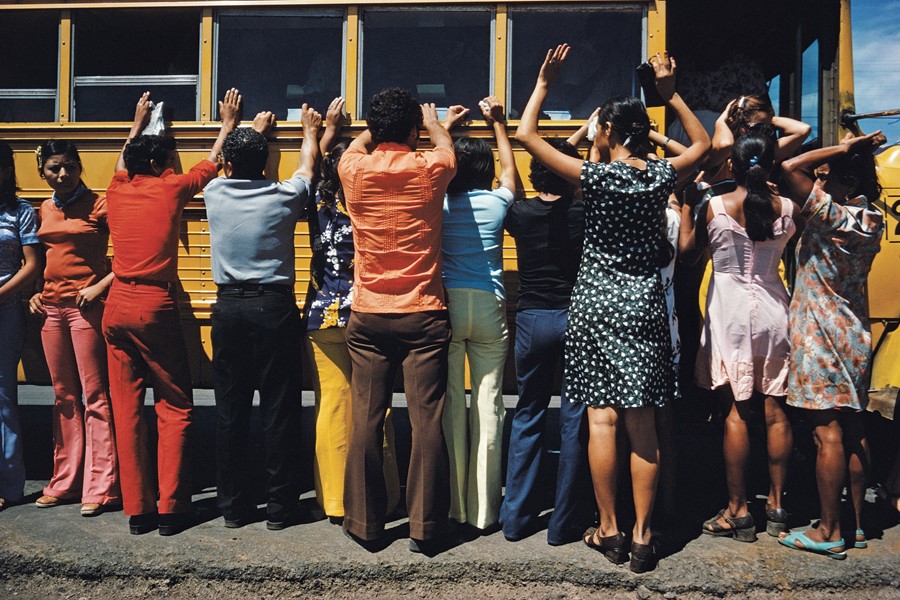

What? Meiselas’ photographs are nothing short of iconic – her image of a Sandinista rebel, colloquially known as Molotov Man, has been appropriated as a global image of insurgency far beyond its original context of the Nicaraguan revolution. Beyond this, her harrowing shots of mass graves, human remains and communities caught up in the crossfire of conflict have graced the pages of Time and the New York Times on countless occasions, revealing the ugliest depths of war and the perilous conditions the wider population faced, with Meiselas often taking huge risks herself. She has been smuggled over the border from Kurdistan, taken shrapnel in El Salvador, and refused to use a 400mm lens provided by her agency when they feared she was getting far too close to imminent danger.

She is also acutely aware of how her work could affect those around her: “The dangers of being involved in this kind of professionalism [are] that you begin to fall short of the responsibilities involved when taking photographs of people who are in danger of losing their lives.” She recalls an incident in Nicaragua, when she discovered that Time had published pictures that showed child rebels’ unmasked faces, despite her previous warning. The magazine was available at her hotel, moments away from government headquarters, and she knew that their discovery could mean death for those pictured. She tried and failed to find and warn the kids, instead trusting the information to a local shopkeeper. “That was the first time that I realised that a photograph could kill.”

Collaborative relationships are at the core of Meiselas’ practice, and set her apart from other photographers who choose to resist proper engagement with the environment that they are hoping to capture. She often records conversations with her subjects and offers her prints as gifts, as well as returning to the sites she has photographed years later, in order to see the progress (or lack thereof) that has occurred.

While on assignment in Portugal she took polaroids of the young immigrant population who were living in semi-illegal settlements, but when she realised that none of her subjects would ever think to enter the museum where her work was exhibited she went back to the neighbourhood and presented blown up versions of the images, for the community to hang wherever they saw fit. She also returned to Nicaragua to find out as much as she could about the people she photographed, resulting in heavily annotated prints that reveal the harsh reality that follows the ideology of revolution.

Why? With the publication of a new book, entitled On the Frontline, Meiselas’ extraordinary feats are brought back to the forefront of popular consciousness, where they deserve to stay. But the philosophy which underpins her work also reaffirms that her audience plays a crucial role in her practice – as witnesses. “Why are circles so special?” she asks in the book. “We are in these triangular relationships, with photographers, subjects and viewers each having pointed and distinct perspectives. The circle is unifying. Everyone is equidistant from the centre. The circle is equalising. At the heart of it is an implicit collaboration. We are all here, looking at each other.”

Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline is out September 2017, published by Thames and Hudson.