Enter the avant-garde universe of Jean Dubuffet, the painter and sculptor inspired by the art of society’s outsiders

Who? “I consider the notion of beauty as completely false,” French avant-garde painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet once said. “I refuse absolutely to assent to this idea that there are ugly persons and ugly objects.” Single-minded, eccentric and rebellious, Dubuffet, who lived from 1901 to 1985, dropped out of art school in his late teens, disillusioned with academic training and the burden of cultural traditions. Although he would set up a studio in his well-to-do parents’ wine depository in Le Havre, it was not until he turned 41 in 1942 that his life as an artist resolutely began.

That year, Dubuffet packed in his job as a wine merchant, and committed himself to making art that prized the uninhibited creativity of children, psychiatric patients, and those who unconsciously defied society and culture’s restrictive customs. Soon, he would dub this kind of work L’Art Brut – raw, naïve art, made by individuals ‘unsmirched’ by artistic or intellectual trends. At a time when war and destruction had brought the role of art into question, and when Pollock was attacking canvases with paint, in Paris Dubuffet was in quest for new and unorthodox methods of representation that would balance the solemnity of tragedy with the need for spontaneity.

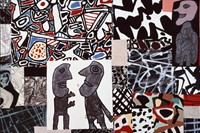

His early paintings indulged in crude materials such as mud, grass, sand and coal, often morphing everyday scenes into fantastical worlds inhabited by purported ‘puppets of the countryside’, lone animals or vagabonds roaming the capital’s Metro. By the 50s, Dubuffet’s childlike, gestural aesthetic (though he hated that term) had sewn the seeds of his signature style, echoing elements of graffiti. Over the next few decades, his puzzle-like prints, paintings, and buoyant sculptures – progressively growing in size – would earn him exhibitions at the Guggenheim, Tate Gallery, and Stejdelijk Museum, among others, cementing Dubuffet as one of the most characterful artists of the 20th century.

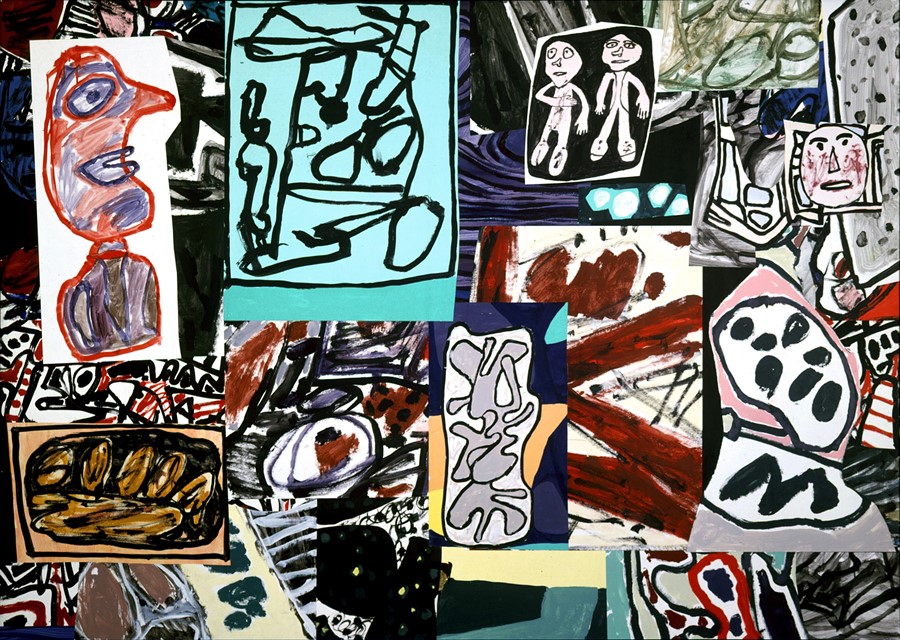

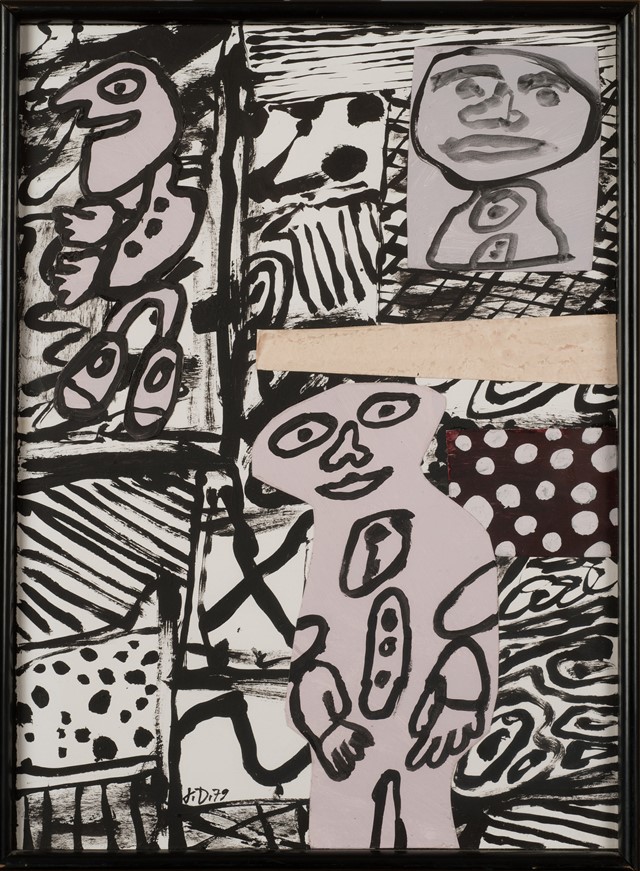

What? Now, a long-awaited exhibition at Pace London, is celebrating Dubuffet’s monumental Théâtre de Mémoires series made between 1975 and 1978. The eight assemblages in this spectacular cycle comprise a dizzying amalgamation of figurative and abstract paintings on paper, each cut out and mounted onto individual canvases in ludic combinations. Dubuffet famously had a huge metal wall installed in his studio so that he could rearrange the cut-out paintings with the help of small magnets. Jam-packed with ideas, his Théâtre represented a trajectory that found the artist not only collect and research art by society’s ‘outsiders’ but also delve into theories of memory and perception.

Frances Yates’ groundbreaking 1966 study into the mental exercises practiced by Roman orators had particular purchase for Dubuffet. Instead of following a chronological order, they would mentally ‘spatialise’ memories like visual constructions. Naturally, the nonconformist artist warmed to this non-linear idea. In a letter to his gallerist Arne Glimtcher, dated 1976, Dubuffet wrote with regard to his Théâtre: “the mind totalises, it recapitulates all fields; it makes them dance together. It shuffles them (…) everything is astir.” Pulling us into the cacophony of his production, Dubuffet ultimately wanted to make viewers see as the mind sees, to liberate perception from narrow ways of viewing.

In his wider work, this urge for multi-layered viewing experiences chimed with the artist’s multi-disciplinary approach. Preceding the Théâtre, his glorious 12-year-long project L’Hourloupe spanned life-size sculptures, paintings and architectural environments, and gave birth to a theatrical production named Cou Cou Bazaar (which looked as kooky as it sounds). The project also included an Instagram goldmine for tourists visiting the Northern town of Périgny: a gargantuan polyurethane-painted garden, proffering viewers a veritable chance to enter his imagination and to live his art.

Why? Like the great artistic minds of the 20th century, from Picasso to Franciszka and Stefan Thermerson, Jean Dubuffet played out his vision across myriad media, creating a universe that was entirely his own. His commitment to thinking outside the box influenced a throng of artists from Keith Haring to Basquiat, but his trademark style – child-like, schematic and graphic – was less concerned with wild and wonderful surfaces than it was with the effects this had on our mind. As Dubuffet claimed, “Too many people think that art addresses the eyes, what poor use that would be!”

There were doubtless contradictions in the artist’s will to create work that targeted the mind, while condemning the intellectualising of art and culture. Still, his aims were well-placed to topple complacent, passive forms of viewing. To this end, Dubuffet played a championing role in opening the first public museum dedicated to L’Art Brut in the Swiss city of Lausanne – an anti-art museum, representing an alternative to the canonical narrative of ‘fail-proof masterpieces’. While scholars, ironically, had little trouble in slipping Dubuffet’s own art into the history books, his legacy is one that will forever honour eccentricity.

Jean Dubuffet: Théâtres de Mémoire runs until October 21, 2017 at Pace Gallery, London.